As far as naval matters goes, the Short Sunderland, was the U-Boat's worst nightmare, equal part and even more than the other allied angel of the Atlantic, the PBY Catalina. This was arguably the most successful Britis flying boat of WW2, for many reasons. Stdied from 1935, bult from 1938 to 1942 and used by many navies (750 built), the last were retired in 1967. A very rugged machine, it gained its nickname of Fliegendes Stachelschwein ("Flying Porcupine") during an engagement by six Ju-88C fighters off Norway in 1940.

It was nicknamed the "Flying Porcupine" by the Germans due to its heavy defensive armament, which made it a challenging target. It had excellent endurance and range, making it well-suited for patrolling vast ocean areas. It was equipped with advanced radar systems later in the war, enhancing its ability to detect and attack submarines. The Sunderland played a crucial role in the Battle of the Atlantic, protecting Allied convoys from German U-boats. It conducted search-and-rescue missions, transport duties, and even cargo runs in remote areas. The aircraft proved rugged and reliable, capable of landing on open water for rescues, though this was risky in rough seas. The Sunderland continued to serve in peacetime roles, including transport and survey missions. Variants were operated by several nations, including Australia, New Zealand, and France. In the early 1930s, there was intense international competition concerning long-range intercontinental passenger service. The main destinations were the United Kingdom and USA, France and Germany or Italy, and in UK, there were concerns that despite having the largest empire, there was no equivalent to the Sikorsky S-42 or German Dornier Do X. In 1934, the British Postmaster General to press forward air transport, declared that all 1st-class Royal Mail overseas would go exclusively by air and a subsidy for the development of intercontinental air transport was initiated. It was hoped this would rise awareness among transporters and spur manufacturers to deliver a good, long range flying boat.

In the early 1930s, there was intense international competition concerning long-range intercontinental passenger service. The main destinations were the United Kingdom and USA, France and Germany or Italy, and in UK, there were concerns that despite having the largest empire, there was no equivalent to the Sikorsky S-42 or German Dornier Do X. In 1934, the British Postmaster General to press forward air transport, declared that all 1st-class Royal Mail overseas would go exclusively by air and a subsidy for the development of intercontinental air transport was initiated. It was hoped this would rise awareness among transporters and spur manufacturers to deliver a good, long range flying boat.

The short S.23 Empire, not the "civilian origin" of the Sunderland, it was more complicated, but the similarities are many

Imperial Airways in that context sent tenders to manufacture 28 large flying boats for mail service. Specifications were precise, specifying 18 long tons and a range of 700 mi (1,100 km) plus 24 passengers. Short Brothers of Rochester, one of the major actor in the flying boat sphere in Britain created for this the Short S.23 Empire. Its role on the later development of the Sunderland was important, but not overwhelming. It set a number of characteristics and solutions that became handy later.

The well named Short Empire was a success, it first flew on 3 July 1936 and 42 were built between 1936 and 1940, first delivered on 22 October 1936, and first revenue flight on 6 February 1937. They were exploited up to WW2 and beyond by the Imperial Airways/BOAC and Qantas Empire Airways. In WW2, they were taken over by respectively the RAAF (11, 13, 20, 33, 41 Sqn.) and RAF's 119 Squadron.

The well named Short Empire was a success, it first flew on 3 July 1936 and 42 were built between 1936 and 1940, first delivered on 22 October 1936, and first revenue flight on 6 February 1937. They were exploited up to WW2 and beyond by the Imperial Airways/BOAC and Qantas Empire Airways. In WW2, they were taken over by respectively the RAAF (11, 13, 20, 33, 41 Sqn.) and RAF's 119 Squadron.

They were narrow, shoulder winged quad-engine monoplanes, with a crew of 5 (2 pilots, navigator, flight clerk and steward), 24 day (seated) passengers or 16 sleeping night passengers plus 1.5 ton of mail. Each was 88 ft (26.82 m) long by 114 ft (34.75 m) in wingspa, and final weight of 23,500 lb (10,659 kg), 40,500 lb (18,370 kg) gross. They were powered by four Bristol Pegasus Xc radial engines, 920 hp (690 kW) each and able to reach 200 mph (320 km/h, 170 kn), cruising at 165 mph (266 km/h, 143 kn) over 760 mi (1,220 km, 660 nmi) and up to 20,000 ft (6,100 m).

From the Short No.1 biplane they went a long way, and in 1911, they buolt a first twin-engine aircraft, the Triple Twin before turning to the new market of naval aircraft floatplanes, starting with the S.26. In WWI their company made their fortune with the mass-produced Type 184. At Gallipolli in 1915 one was the first to drop a torpedo in action from HMS Ben-my-Chree. They also built the successfil patrol flying boats F.3 and F.5 designed by Jogn Porte of Felixtowe. They created a new facility at Borstal, near Rochester, to launch their models on the Medway. They also setup in WWI an Airships factory at Cardington for the admiralty. It was nationalized in 1918 and became the Royal Airship Works.

In 1924 after difficult years producing and designing floats for other manufacturers, they won a contract to produce the Short Singapore followed by the Short Calcutta, all for international routes, before the Short Empire in 1936. The same year the air ministry consolidated this branch and created a new aircraft factory at Belfast, Short & Harland Ltd as it was owned at 50% by famous shipyard Harland and Wolff (of Titanic fame).

Now a few words about the Sarafand: This was a prototype proposed in 1928, built in 1932 as a massive aircraft carrying flying boat and which could double as patrol flying boat for the needs of the RN if needed. Just one was produced in 1932, first flight in June 1932, tested by the RAF bu not adopted. It had six engines in pusher-puller pairs and became the largest fyling boat ever built in Britain.

Now a few words about the Sarafand: This was a prototype proposed in 1928, built in 1932 as a massive aircraft carrying flying boat and which could double as patrol flying boat for the needs of the RN if needed. Just one was produced in 1932, first flight in June 1932, tested by the RAF bu not adopted. It had six engines in pusher-puller pairs and became the largest fyling boat ever built in Britain.

The release of Specification R.2/33 was in advance of the commercial Imperial Airways requirement so when Short received it, with a priority request, they already started planning the design for the military model, and after reviewing both requirements they swapped on the civilian S.23 design while still having people assigned to the RAF spec. R.2/33. It was done under chief designer Arthur Gouge. The latter even suggeedt the mounting of a COW 37 mm gun mounted in the bow and single Lewis gun at the tail for defense. Both designed would have the same fuselage generating the lowest drag but much longer nose.

Saunders-Roe competed with the Saro A.33, and after evaluation of both, the Ministry ordered prototypes for both to perform comparative flight tests for a more detailed evaluation, and choice of awarding one of the two. In April 1936 they selecated Shorts' submission and ordered a firs batch of 11. On 4 July 1936, the first S.23 Short Empire flying boat wasq completed for a maiden flight, immatriculated G-ADHL "Canopus". Its excellent results further proved the choice of the S.25 was the reight one, as discussed in a design conference. In fact it was so promising that the competitive fly-off between the Saro and Short models was abandoned, due to the crash of the sole prototype A.33 due to a structural failure.

The prototype S.25 was still not complete when already several design changes learned from flights of the S.23 were orderd by the ministry. The armament was revised by RAF experts and instead of the single stern 0.303 Vickers K it was decided for a quad 0.303 Browning machine guns in a powered turret. Chief designer Arthur Gouge had to rework its centre of gravity due to this additional weight. Ballast was simply positioned in the forward area and in the end of September 1937, it was ready for trials.

After more flights, the prototype was back in the workshop for extra modification, the Wing sweepback of 4° 15' thanks to a spacer into the front spar attachments. The design change was made to account for changes in defensive armament and repositioned centre of lift to readjust with the centre of gravity in order to accomodate extra armament. This went on with more alterations to maintain the model's hydrodynamics properties. On 7 March 1938, the prototype made its first post-modification flight, the major difference being the new Bristol Pegasus XXII engines now just dellivered and capable delivering a more substantial 1,010 hp (750 kW).

On 21 April 1938, the first Sunderland Mark 1 prototype achieved all its testing goals and was proposed as a model for the 1st development batch. It was transferred to the Seaplane Experimental Station at Felixstowe (Suffolk) for state evaluation at the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment. On 8 March 1938 a second production aircraft arrived and on 28 May 1938, modified this time for tropical conditions it flew for a record-breaking flight to Seletar in Singapore, via Gibraltar, Malta, Alexandria, Habbaniyah, Bahrain, Karachi, Gwalior, Calcutta, Rangoon, and Mergui.

The team abord certified it could be fully refueled in 20 minutes and that the most frugal speed was 130 knots (150 mph; 240 km/h) at 2,000 ft (600 m). It just sucked up 110 imperial gallons per hour (500 L/h) at this regime, giving a record flying time of 18 hours, and for this flight, 2,750 statute miles (4,430 km). The tests also showed it took off over just 680 yd (620 m). This showed the mastery of Short for that fuselage shape and perculiar boat like architecture as the best.

The general structure was all-metal with flush-rivets, as part of flight control surfaces that needed to be accessible ahd were fabric-covered over a metal frame. The flaps had the Short's trademark Gouge-patented systems sliding backwards along curved tracks, or rearwards and downwards to increase the wing area. This system generated a 30% greater lift, for smoother landings.

The thick wings on which were attached the four on-nacelle Bristol Pegasus XXII had six drum-style fuel tanks with a total capacity of 9,200 litres (2,025 Imperial gallons, 2,430 U.S. gallons) which was quite impressive, but they blocked access to the engines. There were even four smaller fuel tanks behind the rear wing spar, added on the Mark II for more range, up to 11,602 litres (2,550 Imperial gallons, 3,037 U.S. gallons) for 14-hour patrols fully armed.

The Pegasus engine was designed by Sir Roy Fedden to replace the Bristol Jupiter, reusing some solutions used for the Mercury. The capacity was smaller at 25 L (15%) but it had the same output shile using supercharging and changes to increase the RPM. This gave it an edge for power-to-weight ratio with an excellent volumetric efficiency. Over time it was pushed from 1,950 to 2,600 rpm for take-off power and from 635 hp (474 kW), to 690 hp (510 kW) and up to the Pegasus XXII's 1,010 hp (750 kW) with a new two-speed supercharger plus 100-octane fuel. In fact the booklet stated "one pound per horsepower".

The most famous user was the Fairey Swordfish, but also multi-engine model such as the 2-engine Vickers Wellington, and the 4-engine Short Sunderland. And other less saviourly models (Like the Bristol Bombay). It was already used on the civilian variant of the Sunderland, the Short Empire. It was also copied by Poland, Italy and Czechoslovakia, for a grand total of over 32,000 Pegasus built. It set height records, notably a flight over Mount Everest and the world's long-distance record.

To boot, the Pegasus was generally reliable, albeit the valves were prone to failure and neede constant check and conscious oiling, especially in hot climates. Also it was not possible to "feather" the propeller. In case of oil failure it would continue to spin by speed alone.

And there was the defensive armament. The tail kept its planned Nash & Thompson FN-13 powered turret and quad .303 British Browning LMGs. This was completed by two manually-operated .303 in flank positions of the fuselage, ports below, behind the wings. In latter Marks, this was change to more hefty 0.5-inch Brownings Heavy machine guns that coud deliver far more punishment.

The nose then received also a powered turret. It was at first a quad Borwning and later twin Browning. Lastly there were four fixed machine guns in the nose that could be fired by the pilot (The COW gun idea was dropped). In furth marks, the twin-gun turret forward was swapped on the dorsal section close to the wing trailing edge, for a grand total of 16 machine guns, two heavy 0.5 inches and 14 0.3 inches. The adoption of US patented machine guns had more to do with ammo supply as the US ramped up its production massively.

The Sunderland had four high power engines, and not only could lift itself, its crew, equipments and gasoline, but also a sizeable bomb and utility offensive load for long patrols. The bombs were loaded in through the "bomb doors", roughly triangular shaped upper half walls just under the main wings. They communicated to the the bomb room on both sides. Bomb racks were sets of transverse rail which could run in and out from the bomb room on tracks, in the underside of the wing on a structural portico. The advantage of the system was that in flight they could be retracted in, doors closed, leaving nothigncausing drag outside. In combat the doorswould open and the bombs or depht charges winched up with their racks to position.

On land for reload, bombs were hoisted up to the extended racks and later lowered to floor stowages and later being prepared for use on the roof retracted racks. The doors were spring-loaded so to pop inwards from their frames, fall under gravity for quick outing of the racks. Release was either locally or remotely by the pilot in a run. The rack sets were limited to 1,000 lb (450 kg) each (generally divided into four bombs or DCs). It was important to drop these equally on both sides to keep balance. After the first drop, the crew installed the next eight weapons loaded just as the pilot was positioning his aircraft for another run.

Apart the points seen above about the hull's underbelly care the engines were pretty standards and needed just average maintenance and n extreme case no maintenance at all apart having oil and gas at all times. These were bulletproof engines, and shared parts with a lot of other models so servicing was not an issue. Plus the nature of these large flying boat was, like the patrol bombers, to be based in UK or close to good facilities given their range. It was more complicated in the Mediterranean though.

-Reworked "step" blow the hull to "unstick" more easily.

-Pegasus XVIII engines with two-speed superchargers rated for 794 kW (1,065 HP).

-Tail turret FN.4A with four 7.7 mm and 2x more ammunition (1,000 rds/gun).

-Late production Mark FN.7 dorsal turret behind the wings, twin 7.7 mm.

December 1941: Sunderland Mark III:

-Revised hull configuration for improved seaworthiness

-Hull "step" to better "unstick" replaced by a smooth curve.

-Empty weight 14,970 kilograms (33,000 pounds), max loaded weight 26,310 kilograms (58,000 pounds)

-Main variant, mass production of 461 by Short Rochester, Belfast, Lake Windemere (new plant) as well as 170 by Blackburn.

Mid-1942:

-Adoption of the ASV Mk III radar replacing the Mzrk II, detected by U-Boat Metox systems (Mark IIIa).

-4+ machine guns, fixed forward fuselage for the Pilot to strafe U-Boats.

-2x 0.50 (12.7 mm) guns either side. on Mark Is (retrofit)

-Adoption of hydrostatically fused 250 lb (110 kg) depth charges

-Adoption of ammunition boxes of 10 and 25 lb (5 and 11 kg) anti-personnel bombs to hit FLAK

-Optimisations for night patrols but no Leigh lights.

-Instead, 1-in (25.4 mm), electrically initiated flares, dropped via rear chute

Thes engines also turned the propeller too fast and were replaced by new, larger Hamilton Standard's Hydromatic constant-speed and fully feathering propellers, whjch was not possible before. The Mark V as a result had greater performance and kept the same range. In fact they were so powerful that even with two engines down, the Sunderland would stay in the air and not experience a drop in altitude. Production thus was switched and Twin Wasp obtained. However the whole process lasted for a year. It's only in February 1945 that the first Mark V reached the frontline. Armament did not changed bu these adopted the new centimetric ASV Mark VI C radar. 155 Sunderland were made, 33 Mark IIIs converted before contracts were cancelled. Though with so many hulls still on construction, the last ones were still delivered as late as June 1946 for a grand total of 777, versus 756 in wartime.

The RAF received its first Sunderland Mark I in June 1938. The second produced flew to Singapore. By September 1939, the RAF Coastal Command operated 40 Sunderlands Mark I. Before ASW organization was setup, Sunderlands were used for search and rescue of crews of torpedoed ships. On 21 September 1939, two Sunderlands rescued 34 from KENSINGTON COURT in heavy seas. As ASW organization progressed, theur performances against U-Boats also did. It's an RAAF (Royal Australian Air Force) Sunderland which in fact scored the first registered U-Boat kill of the war on 17 July 1940. As Sunderlands became more common over the seas, their encountered with the Lufwaffe went up as well. On 3 April 1940, while off Norway the most famous encountered solidified the legend of this new flying boat. Long story short, the lone Mark I was attacked by no less than six German Junkers Ju 88 fighters, fitted woth a nose with MGs and a cannon. It managed to shoot one down, damage another (forced landing) and drove off the rest. If at their return the Germans nicknamed it the "Fliegende Stachelschwein (Flying Porcupine)" the written source however was never found.

Sunderlands also found their use in the brighter Mediterranean and even performed better to a point. Their engines suffered greatly however; They notably evacuated countles troops during the evacuations after the German invasion of Crete, while it's a Sunderland that reported the Regia Marina's position at anchor in Taranto before the famous 11 November 1940 night raid by Swordfishes. Another day, also off Crete, one Sunderland broke the record book by rescuing no less than 82 men in one go, on a calm sea. All in all, the Sunderland was used by the No. 10, 40 and 461 Squadron RAAF, between the Med and Pacific, but also the 422-423 Sqn. RCAF, 5 and 490 Squadron RNZAF, No.35 Squadron SAAF, and No. 330 Squadron RNoAF (Norwegian crews) and the Free French No. 343 Squadron RAF, later Escadrille 7FE and postwar, notaby in Indochina, the Flottille 1FE, 7F, 27F, 12S, 50S, 53S, mostly Mark Vs for the latter. Commonality of engines with the Catalina and Dakota were much appreciated. The RAF Coastal Command operated them in the No. 8, 95, 119, 201, 202, 204, 205, 209, 210, 228, 230, 240, 246, 259, 270 Sqn. and the 235 Operational Conversion Unit RAF.

As the war intensified in the Atlantic, so the Sunderland, the numerous Mark IIIs in particular went up to higher gear to relentless hunts over long hours. Thanks to their max 13h flights, pilots tried to reach the "black pot" where the range of air cover and of some destroyers generally stopped. From October 1941, Sunderlands were fitted with ASV Mark II "Air to Surface Vessel" radar, a primitive low frequency system with a wavelength of just 1.5 m connected to "stickleback" Yagi antennas on top of the rear fuselage with four smaller in two rows along the sides. There was a single receiving aerial under each wing outboard of the float, angled outward as well and other systems appered over the years. They proved more and more able to detect U-Boats in appealing weather, the norm in the north Atlantic. Sunderland pilots indeed braves the winter, so confident they were in their massive machines.

However by mid-1942 the Germans started to bring up counter-measures. Some U-Boat were equipped with the passive Metox radar detection device and were alerted by the proximity of a sunderland. This gave them time to dive. Once the new detector started to be generalized, sightings just dropped drastically. However another measure was more radical and enabled the U-Boats to stay longer and even not diving at all: Heavy FLAK. Most carried twin 20 mm AA guns and later the VIIC/M42 had a 37 mm and up to four 20 mm, not counting the "U-FLAK" that were deployed as well. Against this, the Sunderland were armed as well. The cal. .05 M1920 Browning heavy machine guns located in the flanks could be used as anti-personal weapons and the late Mark III pilots also received four LMGs in the nose to strafe the U-boat before a low altitude bombing pass. Later, they also received anti-personal grenades just to harrass the crews.

In 1943-44, the fight even intensified at night with rolling patrols of alternative aicraft per squadrons or even specialized night squadrons. They came equipped with flares and better radars, notably some that could not be intercepted by U-Boats. U-Boats mostly stayed surfaced by night and just caught up with convoys when starting their attacks, diving only when they had no other choice. Sunderland crews were briefed by Convoys captains to circle around certain positions were U-Boats wen known to gather and changes their tactics on the fly (pun intended) for better results. When a Sunderland was around, captains were condifent that a ship left behind, torpedoed would have its crew picked up rapidly by the four-engines guardian angel.

The Mark V was designed to fight in the Pacific but overall saw little service in it. A few were sent from 1941 and when the Mark V production ramped up, a few squadrons were constituted but IJN submarine activity was all but gone. Instead, Sunderlands mostly performed SAR missions, picking up pilots in particular in and around the late combat theaters, in particular Okinawa and during the last Australian and commonwealth operations notably in Burma-Malaya, especially as transports. On that chapter as the war in Europe ended, more and more were converted as transports, unarmed.

In late 1942 already the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) obtained six Mark IIIs, de-militarised as mail carriers to Nigeria and India. They could carry either 22 passengers and 2 tons of freight or 16 passengers and 3 tons of freight. They were also used by RAF as VIP transports from Poole to Lagos and Calcutta. Six more Mark IIIs were obtained in 1943 and performed better for cruise speed. By late 1944, the RNZAF acquired four Mk IIIs already modified for transport and postwar they were used by New Zealand's National Airways Corporation on the "Coral Route" until 1947.

Many companies bought stocked Sunderlands postwar a low price. BOAC obtained much more demilitarized Mark IIIs and made better accommodations in three configurations. One had a promenade deck, another had 24 seats, even 16 sleeping berths. 29 of these flew in 1945. In February 1946, one made a record 35,313-mile survey from Poole to Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Tokyo (206 flying hours), a record at the time. The company improved on its model which gave the postwar Short Sandringham. The Mk.I had earlier Pegasus engines, the Mk.II Twin Wasp engines (like the Mark III and Mark V). verall postwar they were used by the Aerolíneas Argentinas, Ansett Flying Boat Services, Antilles Airboats (US Virgin Islands), Aquila Airways, Compañía Aeronáutica Uruguaya S.A. (CAUSA), Compañía Argentina de Aeronavegación Dodero, Det Norske Luftfartselskap (DNL), Qantas, Trans Oceanic Airways, TEAL (Tasman Empire Airways Ltd, New Zealand).

-ML824 in Hangar 1 RAF Museum London Hendon, ex-French Navy, left Brest to Pembroke on 24 Mar 1961.

-ML796 t Imperial War Museum Duxford in Cambridgeshire.

-NJ203 RAF Mark IV/Seaford I S-45 NJ203. at Oakland Aviation Museum, Cal.

-NZ4111 at the Chatham Islands. ex RNZAF until 1959.

-NZ4112 Hulk at Hobsonville Yacht Club until 1970, Cockpit and front now at Ferrymead Aeronautical Society Inc. Christchurch NZ

-NZ4115 previous BOAC G-AHJR at the Museum of Transport and Technology in Auckland, New Zealand.

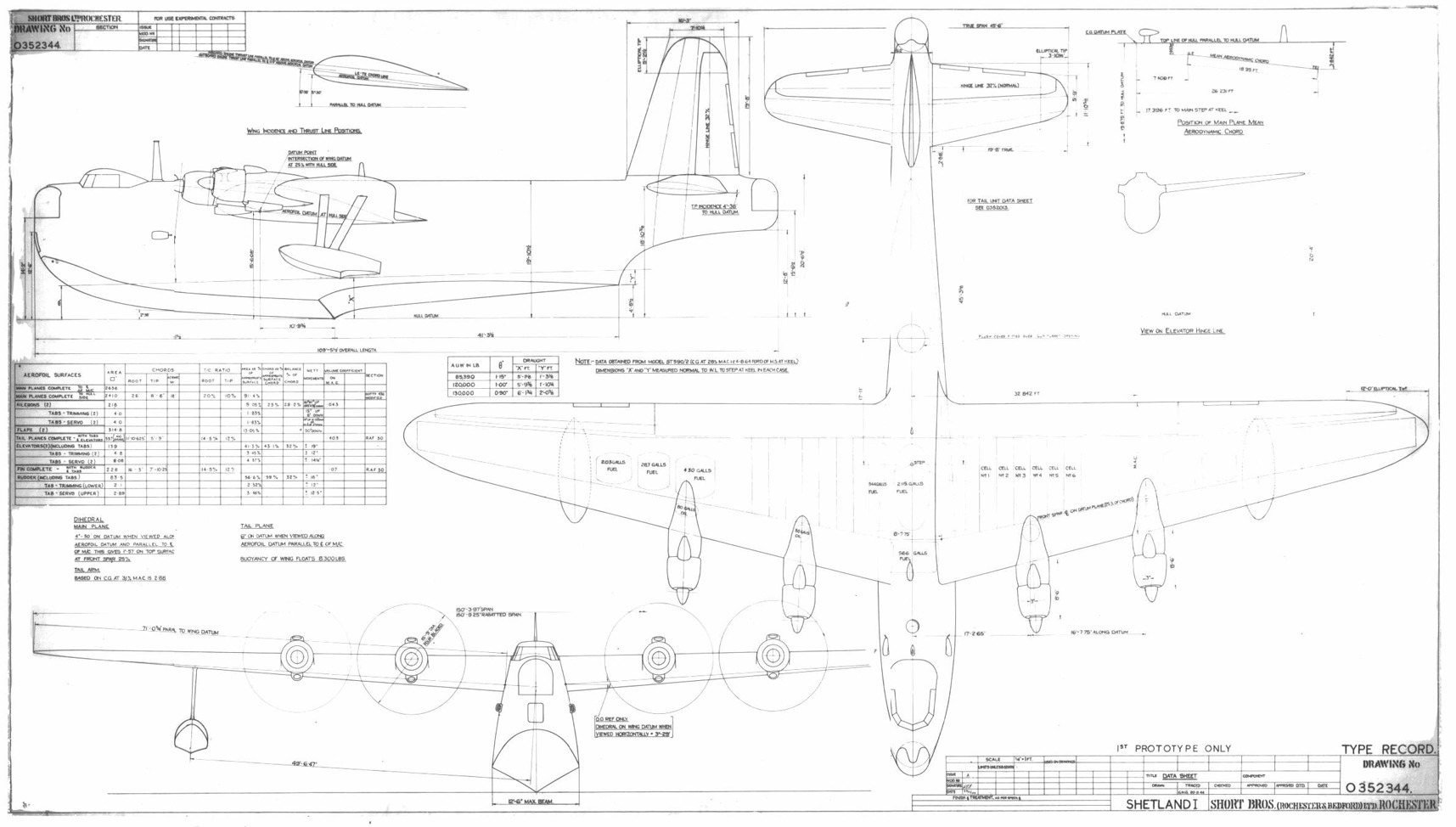

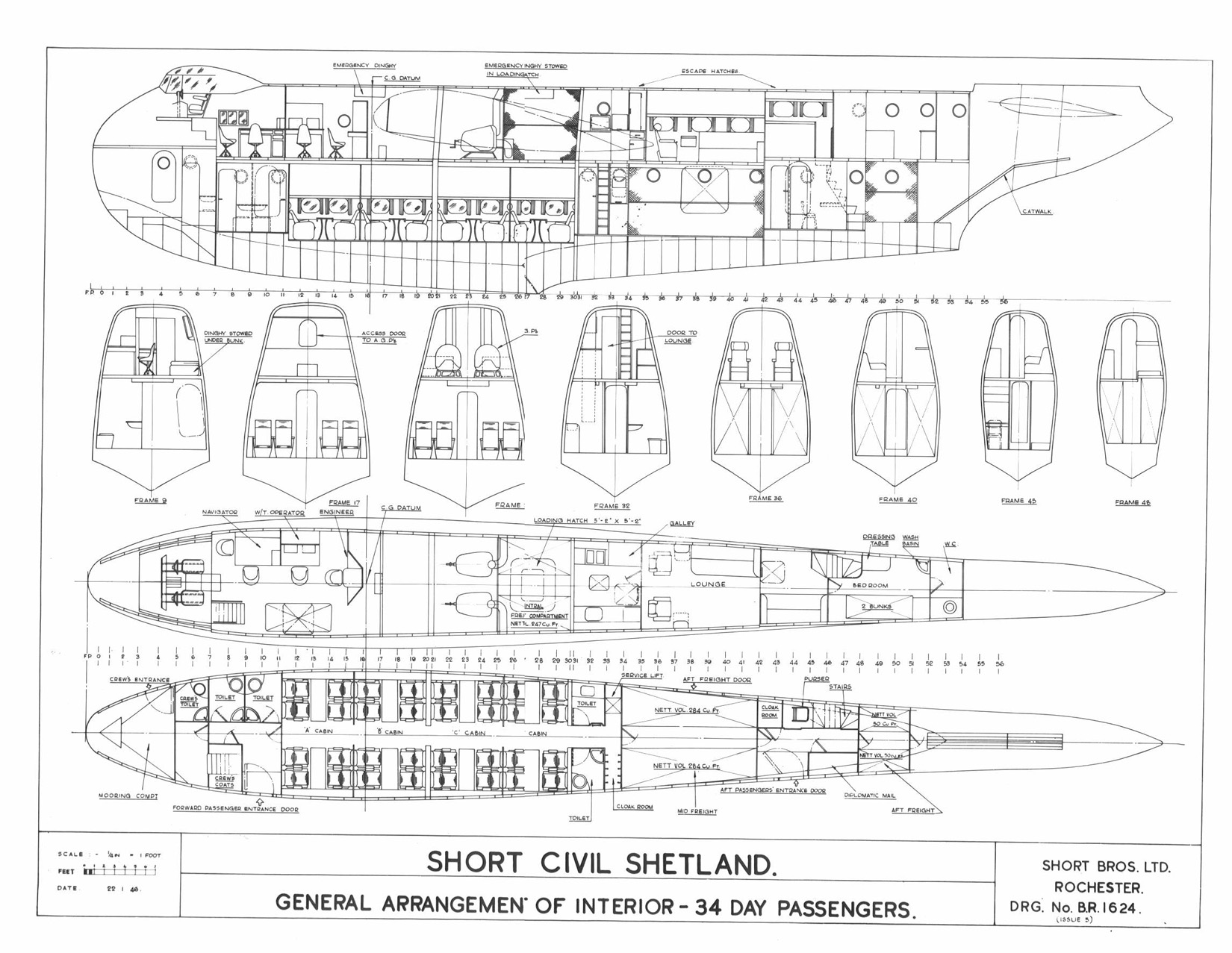

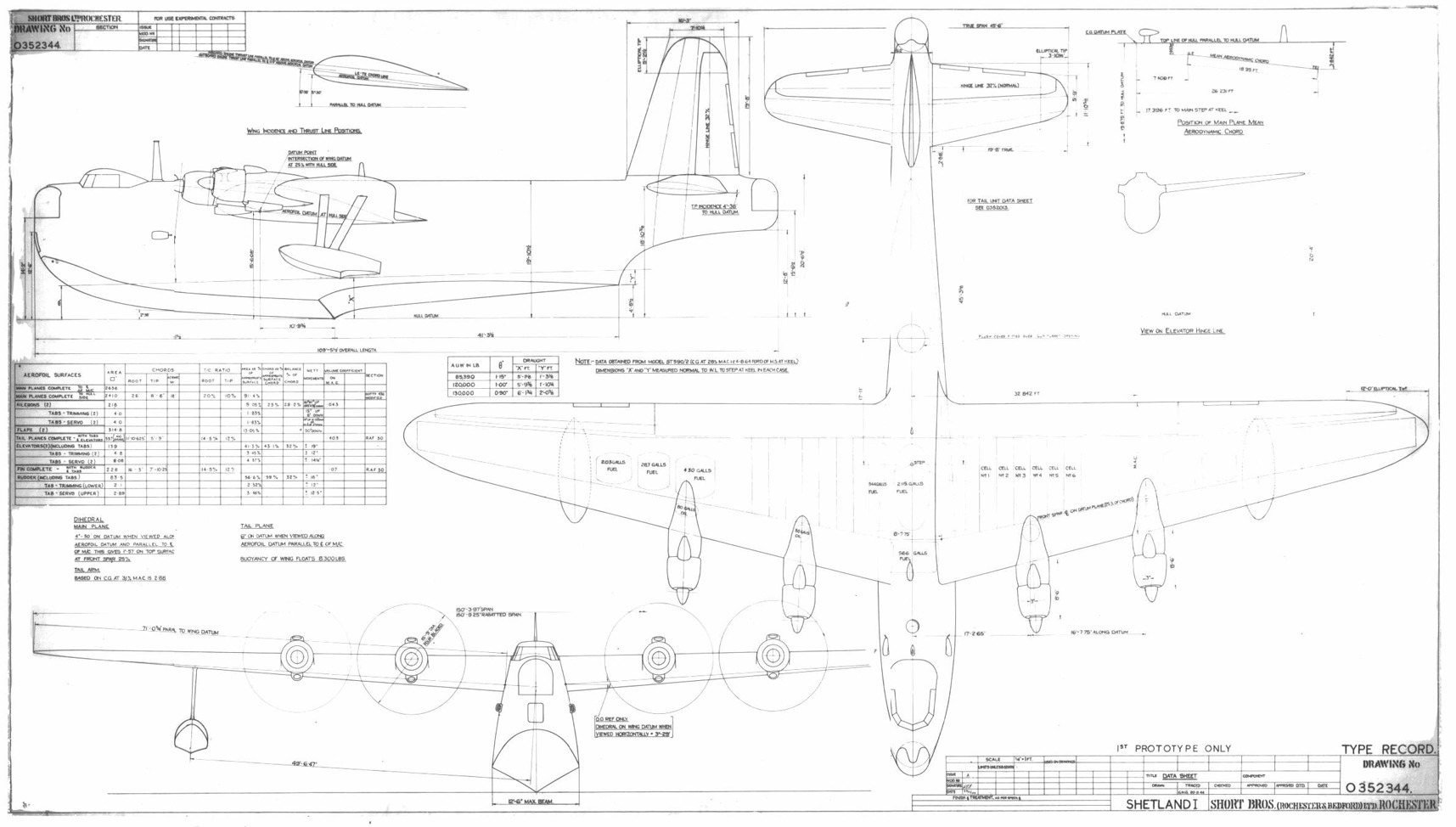

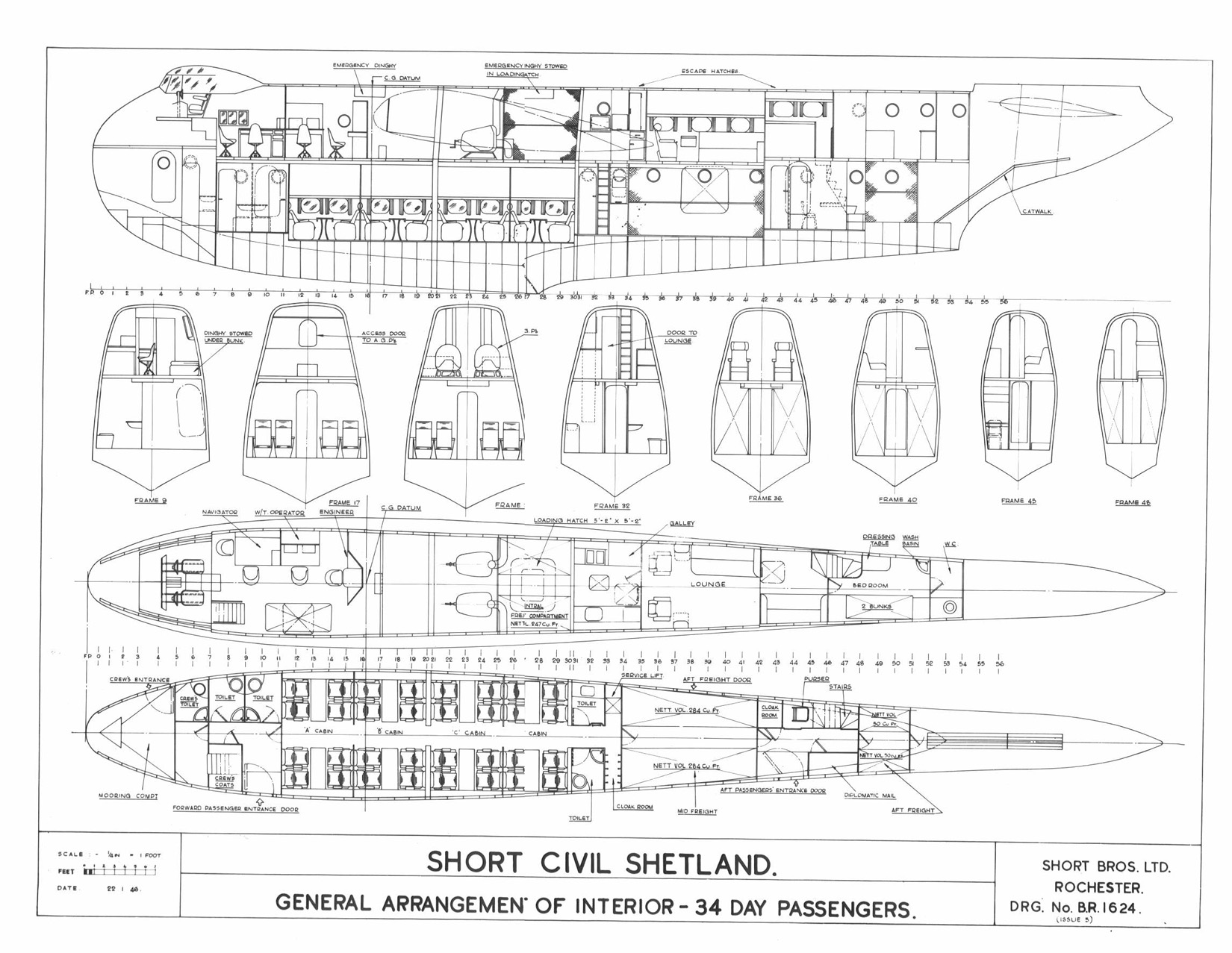

The SHORT SHETLAND was a planned successor of the Sunderlmand. This was a High-speed, very long-range, heavily-armed reconnaissance flying-boat. Internally it was called Short S.35; designed to OR.91, in compliance with Specification R. 14/40. Two prototypes were ordered after selection of Short design in favour of competing Saro S.41, Saro being made responsible for detail design and manufacture of wing. First flight was on December 14, 1944, with the prototype DX166. It was at that stage largest British aircraft to have flown.

It was powered by four 2,400 hp Bristol Centaurus VII engines, with a crew of 11, armed with nose, dorsal and tail turrets with at least a pair of 0.50-in (12.7-mm) heavy MGs each, and a massive bomb load of 18,000 Ib (8,165 kg). The war ended before completion of the second prototype. Top speed was superior to the Sunderland at 263 mph (424 km/h) despite a gross weight of 125,000 Ib (56,700 kg). Its record span was of 150ft 4 in (46.75 m) for 110 ft (33.5 m) long. The tail, floats, struts and many parts were borrowed from the Sunderland.

Plans

In short

The Short Sunderland was a British flying boat and one of the most iconic maritime patrol aircraft of World War II. It was designed and built by Short Brothers, entering service in 1938, and remained operational in various roles until the 1960s. This was a long-range maritime reconnaissance and anti-submarine warfare (ASW), high-wing monoplane flying boat with four engines, a deep hull, and large fuel capacity for extended missions. The Crew was typically 7–11 personnel, depending on mission requirements. It was well defended with Multiple .303 Browning machine guns mounted in powered turrets (nose, tail, and dorsal positions). It carried also Bombs, depth charges, or mines carried under the wings.It was nicknamed the "Flying Porcupine" by the Germans due to its heavy defensive armament, which made it a challenging target. It had excellent endurance and range, making it well-suited for patrolling vast ocean areas. It was equipped with advanced radar systems later in the war, enhancing its ability to detect and attack submarines. The Sunderland played a crucial role in the Battle of the Atlantic, protecting Allied convoys from German U-boats. It conducted search-and-rescue missions, transport duties, and even cargo runs in remote areas. The aircraft proved rugged and reliable, capable of landing on open water for rescues, though this was risky in rough seas. The Sunderland continued to serve in peacetime roles, including transport and survey missions. Variants were operated by several nations, including Australia, New Zealand, and France.

Development

In the early 1930s, there was intense international competition concerning long-range intercontinental passenger service. The main destinations were the United Kingdom and USA, France and Germany or Italy, and in UK, there were concerns that despite having the largest empire, there was no equivalent to the Sikorsky S-42 or German Dornier Do X. In 1934, the British Postmaster General to press forward air transport, declared that all 1st-class Royal Mail overseas would go exclusively by air and a subsidy for the development of intercontinental air transport was initiated. It was hoped this would rise awareness among transporters and spur manufacturers to deliver a good, long range flying boat.

In the early 1930s, there was intense international competition concerning long-range intercontinental passenger service. The main destinations were the United Kingdom and USA, France and Germany or Italy, and in UK, there were concerns that despite having the largest empire, there was no equivalent to the Sikorsky S-42 or German Dornier Do X. In 1934, the British Postmaster General to press forward air transport, declared that all 1st-class Royal Mail overseas would go exclusively by air and a subsidy for the development of intercontinental air transport was initiated. It was hoped this would rise awareness among transporters and spur manufacturers to deliver a good, long range flying boat.

The Short Empire

The short S.23 Empire, not the "civilian origin" of the Sunderland, it was more complicated, but the similarities are many

Imperial Airways in that context sent tenders to manufacture 28 large flying boats for mail service. Specifications were precise, specifying 18 long tons and a range of 700 mi (1,100 km) plus 24 passengers. Short Brothers of Rochester, one of the major actor in the flying boat sphere in Britain created for this the Short S.23 Empire. Its role on the later development of the Sunderland was important, but not overwhelming. It set a number of characteristics and solutions that became handy later.

The well named Short Empire was a success, it first flew on 3 July 1936 and 42 were built between 1936 and 1940, first delivered on 22 October 1936, and first revenue flight on 6 February 1937. They were exploited up to WW2 and beyond by the Imperial Airways/BOAC and Qantas Empire Airways. In WW2, they were taken over by respectively the RAAF (11, 13, 20, 33, 41 Sqn.) and RAF's 119 Squadron.

The well named Short Empire was a success, it first flew on 3 July 1936 and 42 were built between 1936 and 1940, first delivered on 22 October 1936, and first revenue flight on 6 February 1937. They were exploited up to WW2 and beyond by the Imperial Airways/BOAC and Qantas Empire Airways. In WW2, they were taken over by respectively the RAAF (11, 13, 20, 33, 41 Sqn.) and RAF's 119 Squadron.

They were narrow, shoulder winged quad-engine monoplanes, with a crew of 5 (2 pilots, navigator, flight clerk and steward), 24 day (seated) passengers or 16 sleeping night passengers plus 1.5 ton of mail. Each was 88 ft (26.82 m) long by 114 ft (34.75 m) in wingspa, and final weight of 23,500 lb (10,659 kg), 40,500 lb (18,370 kg) gross. They were powered by four Bristol Pegasus Xc radial engines, 920 hp (690 kW) each and able to reach 200 mph (320 km/h, 170 kn), cruising at 165 mph (266 km/h, 143 kn) over 760 mi (1,220 km, 660 nmi) and up to 20,000 ft (6,100 m).

Short Brother's story and Models

Short Brothers plc, from Belfast, Northern Ireland was originally founded in 1908 in London. Its debut where with balloons in 1897, Eustace Short (1875 – 1932), the older brother of three, buying a second-hand coal gas filled balloon and with his brothers started to develop and manufacture balloons. In 1900 at the Paris Exposition they adopted the new Astra style construction, and started to sell them in 1902, having a large contract for the British Indian Army in 1905. In 1908 convinced aeroplanes were the future they managed to convince their brother Eustace which left for Parsons, working on steam turbines. The new company is born in Nov. 1908 and started limited production for the Aero Club. They were the centerpeice of the 1909 first British Aero Show.From the Short No.1 biplane they went a long way, and in 1911, they buolt a first twin-engine aircraft, the Triple Twin before turning to the new market of naval aircraft floatplanes, starting with the S.26. In WWI their company made their fortune with the mass-produced Type 184. At Gallipolli in 1915 one was the first to drop a torpedo in action from HMS Ben-my-Chree. They also built the successfil patrol flying boats F.3 and F.5 designed by Jogn Porte of Felixtowe. They created a new facility at Borstal, near Rochester, to launch their models on the Medway. They also setup in WWI an Airships factory at Cardington for the admiralty. It was nationalized in 1918 and became the Royal Airship Works.

In 1924 after difficult years producing and designing floats for other manufacturers, they won a contract to produce the Short Singapore followed by the Short Calcutta, all for international routes, before the Short Empire in 1936. The same year the air ministry consolidated this branch and created a new aircraft factory at Belfast, Short & Harland Ltd as it was owned at 50% by famous shipyard Harland and Wolff (of Titanic fame).

Specification R.2/33

By November 1933, the British Air Ministry released Specification R.2/33. This called for a next-generation long-range general purpose flying boat for ocean reconnaissance and could be either a monoplane or biplane and at least equal in performances to the Short Sarafand flying boat, and to be powered by a maximum of four engines, while being more compact than the Sarafand. Now a few words about the Sarafand: This was a prototype proposed in 1928, built in 1932 as a massive aircraft carrying flying boat and which could double as patrol flying boat for the needs of the RN if needed. Just one was produced in 1932, first flight in June 1932, tested by the RAF bu not adopted. It had six engines in pusher-puller pairs and became the largest fyling boat ever built in Britain.

Now a few words about the Sarafand: This was a prototype proposed in 1928, built in 1932 as a massive aircraft carrying flying boat and which could double as patrol flying boat for the needs of the RN if needed. Just one was produced in 1932, first flight in June 1932, tested by the RAF bu not adopted. It had six engines in pusher-puller pairs and became the largest fyling boat ever built in Britain.

The release of Specification R.2/33 was in advance of the commercial Imperial Airways requirement so when Short received it, with a priority request, they already started planning the design for the military model, and after reviewing both requirements they swapped on the civilian S.23 design while still having people assigned to the RAF spec. R.2/33. It was done under chief designer Arthur Gouge. The latter even suggeedt the mounting of a COW 37 mm gun mounted in the bow and single Lewis gun at the tail for defense. Both designed would have the same fuselage generating the lowest drag but much longer nose.

Selection and modifications

In October 1934, Shorts settled upon its general configuration, with the four-engine being shoulder-wing mounted (monoplane configuration) like for the Short Empire. The military variant was called internally S.25 and looked quite close to the S.23, but with an improved aerodynamic form and better general curvature, as a compound curve. It was refined with a model in a wind tunnel to really iron out a perfect shape. By late 1934, the S.25 proposal was submitted to the Air Ministry.Saunders-Roe competed with the Saro A.33, and after evaluation of both, the Ministry ordered prototypes for both to perform comparative flight tests for a more detailed evaluation, and choice of awarding one of the two. In April 1936 they selecated Shorts' submission and ordered a firs batch of 11. On 4 July 1936, the first S.23 Short Empire flying boat wasq completed for a maiden flight, immatriculated G-ADHL "Canopus". Its excellent results further proved the choice of the S.25 was the reight one, as discussed in a design conference. In fact it was so promising that the competitive fly-off between the Saro and Short models was abandoned, due to the crash of the sole prototype A.33 due to a structural failure.

The prototype S.25 was still not complete when already several design changes learned from flights of the S.23 were orderd by the ministry. The armament was revised by RAF experts and instead of the single stern 0.303 Vickers K it was decided for a quad 0.303 Browning machine guns in a powered turret. Chief designer Arthur Gouge had to rework its centre of gravity due to this additional weight. Ballast was simply positioned in the forward area and in the end of September 1937, it was ready for trials.

S.25 flight tests

On 16 October 1937, S.25 prototype K4774 started her maiden flight. The four Bristol Pegasus X radials rated for 950 hp (710 kW) were started. This was not the first choice of the ministry but the intended Pegasus XXII was unavailable. The prototype took off with chief test pilot John Lankester Parker and Harold Piper, and they proceeded to slow turns for 45 minutes. Next a second flight was performed and at the end of the day, Parker declared declared the model was as good as the Short Empire and behaved about the same way, albeit more sluggish. In the meantime, the RAF called the new model the "Sunderland", after the port in North East England.After more flights, the prototype was back in the workshop for extra modification, the Wing sweepback of 4° 15' thanks to a spacer into the front spar attachments. The design change was made to account for changes in defensive armament and repositioned centre of lift to readjust with the centre of gravity in order to accomodate extra armament. This went on with more alterations to maintain the model's hydrodynamics properties. On 7 March 1938, the prototype made its first post-modification flight, the major difference being the new Bristol Pegasus XXII engines now just dellivered and capable delivering a more substantial 1,010 hp (750 kW).

On 21 April 1938, the first Sunderland Mark 1 prototype achieved all its testing goals and was proposed as a model for the 1st development batch. It was transferred to the Seaplane Experimental Station at Felixstowe (Suffolk) for state evaluation at the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment. On 8 March 1938 a second production aircraft arrived and on 28 May 1938, modified this time for tropical conditions it flew for a record-breaking flight to Seletar in Singapore, via Gibraltar, Malta, Alexandria, Habbaniyah, Bahrain, Karachi, Gwalior, Calcutta, Rangoon, and Mergui.

The team abord certified it could be fully refueled in 20 minutes and that the most frugal speed was 130 knots (150 mph; 240 km/h) at 2,000 ft (600 m). It just sucked up 110 imperial gallons per hour (500 L/h) at this regime, giving a record flying time of 18 hours, and for this flight, 2,750 statute miles (4,430 km). The tests also showed it took off over just 680 yd (620 m). This showed the mastery of Short for that fuselage shape and perculiar boat like architecture as the best.

Design

General conception

The Short S.25 Sunderland borrowed much from the S.23 but with more powerful engines anf a deeper hull profile. Its interior was so roomy as to be separated in two individual decks: The lower deck comprised six bunks for passengers and a galley with a twin kerosene pressure stove for meals in glights, and even a yacht-style porcelain flush toilet. There was an anchoring winch in the nose and a small machine shop for in-flight repairs. Of the seven members of the complement intended, later versions saw it grew to 11 or more depending of the missions and armaments upgrades.The general structure was all-metal with flush-rivets, as part of flight control surfaces that needed to be accessible ahd were fabric-covered over a metal frame. The flaps had the Short's trademark Gouge-patented systems sliding backwards along curved tracks, or rearwards and downwards to increase the wing area. This system generated a 30% greater lift, for smoother landings.

The thick wings on which were attached the four on-nacelle Bristol Pegasus XXII had six drum-style fuel tanks with a total capacity of 9,200 litres (2,025 Imperial gallons, 2,430 U.S. gallons) which was quite impressive, but they blocked access to the engines. There were even four smaller fuel tanks behind the rear wing spar, added on the Mark II for more range, up to 11,602 litres (2,550 Imperial gallons, 3,037 U.S. gallons) for 14-hour patrols fully armed.

Engines

The Pegasus engine was designed by Sir Roy Fedden to replace the Bristol Jupiter, reusing some solutions used for the Mercury. The capacity was smaller at 25 L (15%) but it had the same output shile using supercharging and changes to increase the RPM. This gave it an edge for power-to-weight ratio with an excellent volumetric efficiency. Over time it was pushed from 1,950 to 2,600 rpm for take-off power and from 635 hp (474 kW), to 690 hp (510 kW) and up to the Pegasus XXII's 1,010 hp (750 kW) with a new two-speed supercharger plus 100-octane fuel. In fact the booklet stated "one pound per horsepower".

The most famous user was the Fairey Swordfish, but also multi-engine model such as the 2-engine Vickers Wellington, and the 4-engine Short Sunderland. And other less saviourly models (Like the Bristol Bombay). It was already used on the civilian variant of the Sunderland, the Short Empire. It was also copied by Poland, Italy and Czechoslovakia, for a grand total of over 32,000 Pegasus built. It set height records, notably a flight over Mount Everest and the world's long-distance record.

To boot, the Pegasus was generally reliable, albeit the valves were prone to failure and neede constant check and conscious oiling, especially in hot climates. Also it was not possible to "feather" the propeller. In case of oil failure it would continue to spin by speed alone.

Armament

The initial specification called for a 37 mm gun plus 2,000 lb (910 kg) of bombs or mines and later depth charges, the latter being stored inside the fuselage. They were placed in a purpose-built bomb room for setup, especially the depth charge. They were then winched up to racks under the wing centre section, through an enclosed trap while in flight to avoid air ingress. Access to armament from inside was a crucial advantage.And there was the defensive armament. The tail kept its planned Nash & Thompson FN-13 powered turret and quad .303 British Browning LMGs. This was completed by two manually-operated .303 in flank positions of the fuselage, ports below, behind the wings. In latter Marks, this was change to more hefty 0.5-inch Brownings Heavy machine guns that coud deliver far more punishment.

The nose then received also a powered turret. It was at first a quad Borwning and later twin Browning. Lastly there were four fixed machine guns in the nose that could be fired by the pilot (The COW gun idea was dropped). In furth marks, the twin-gun turret forward was swapped on the dorsal section close to the wing trailing edge, for a grand total of 16 machine guns, two heavy 0.5 inches and 14 0.3 inches. The adoption of US patented machine guns had more to do with ammo supply as the US ramped up its production massively.

Navigation

Mooring

Being a flying boat, the Sunderland wa sprovided with all that can sustain its own nautical service. One as control and the other was mooring. The Sunderland had standard ship navigation lights, red and green, and a collapisble mooring mast positioned on the upper fuselage, aft of the astrodome hatch. It was coupled with a 360-degree white light activated when moored. Crewmembers were trained to master marine signals for extra safety in crowded waters. It could be moored to a buoy by a pendant attached to the keel and when off its forward end was attached to the front of the hull. There was also a demountable bollard fixed to the forward fuselage. The front turret was retracted, allowing the airman to man the positio, pick up the buoy cage or toss out the anchor.Steering (Drogues)

For taxiing, galley hatches could be used to extend sea drogues to turn the Sunderland underway, or maintain its crosswind and slow forward motion when deployed on both sides counter-wind. They were hand hauled back inboard and folded at great effort when soaking wet, then stowed in wall-mounted containers below the hatches. These three-foot-diameter devices would haul up on their 5-tonne pull attachment cable inside the galley, enough to sever a limb if caught in between. Once deployed, it was difficult to recover it until the aircraft was stopped and with no wind, and then with some extra arms.Steering (engines and controls)

When the engines were on, the pilot would use its rudder and aileron flight controls to cause asymmetric lift, which would drop a float into the water and drag that wing, turning the aircraft. Varying engine power for direction and speed were however limited on case of adverse tide, wind, and destination.Beaching

One of the great advantages of the Sunderland was to be beached everywhere. The underbelly was strongly built, well enough to support the structural strain of a had sea landing or bouncujg at take off (at high speed the sea is as compact as reinforced concrete). So there was no issue on that matter. PThere was a portable beaching gear which would be used to secure the aircraft and pull it up further on land and avoid tide refloating issues. The gear comprised two-wheeled struts attached on one end to both sides of the fuselage below the wing at a structure point. Then, at the other end a 2-4 wheel trolley and towbar would be attached under the rear of the hull. It could then be winched up.Anchoring

The Short Sunderland was fitted with a standard stocked anchor, stowed in the forward compartment near the corresponding anchor winch. Different anchor types were provided to adapt to different anchorages.Maintenance and Service

Access and exit

The crew entered the Sunderland via the left forward bow compartment door. The internal compartments comprised the bow, gun room, ward room, galley, bomb room and the after compartments all enclosed like on a ship by transverse bulkheads with swash doors. This helped to keep and excellent buoyancy, as the flying boat needed to remain watertight to about two feet (610 mm) above normal water level and thus these doors remained closed. The other external door was in the tail compartment, right side. The right-left access enabled to exit the fuselage if laying sideways, wings gone. This door was intended to access via a U-shaped pontoon ("Braby"), inheritance of the civilian design for full passenger service mooring. It was large enough to allow the transit of stretcher-bound patients while in open water. It wa salso used when the engines were kept running to keep position for an approaching vessel. The front door indeed was too close to the left inboard propeller. There was also a third access, through the astrodome hatch, front spar, wing centre section, rear of the navigator's station.Armament service

The numerous machine guns in powered turrets, nose, tail, and dorsal for post-Mark I versions, could be completed by extra flank position servicing a single cal.05 Browning heavy machine gun. Its firepower all combined could reach 16 weapons, including the fixed ones in the fuselage aimed by the pilots and used fo strafe U-Boats. All these gun positions had access to immediate reload ammo boxes, but extra boxes could be stored in a special bin inside the fuselage. The latter had flanks with double walls filled by water.The Sunderland had four high power engines, and not only could lift itself, its crew, equipments and gasoline, but also a sizeable bomb and utility offensive load for long patrols. The bombs were loaded in through the "bomb doors", roughly triangular shaped upper half walls just under the main wings. They communicated to the the bomb room on both sides. Bomb racks were sets of transverse rail which could run in and out from the bomb room on tracks, in the underside of the wing on a structural portico. The advantage of the system was that in flight they could be retracted in, doors closed, leaving nothigncausing drag outside. In combat the doorswould open and the bombs or depht charges winched up with their racks to position.

On land for reload, bombs were hoisted up to the extended racks and later lowered to floor stowages and later being prepared for use on the roof retracted racks. The doors were spring-loaded so to pop inwards from their frames, fall under gravity for quick outing of the racks. Release was either locally or remotely by the pilot in a run. The rack sets were limited to 1,000 lb (450 kg) each (generally divided into four bombs or DCs). It was important to drop these equally on both sides to keep balance. After the first drop, the crew installed the next eight weapons loaded just as the pilot was positioning his aircraft for another run.

Maintenance

The large floats mounted under each wing maintained stability, one almost always deeper and if one broke off, when lainding the crew would gather on the otherr sode to compensate and avoid the opposing floatless wing to hit water. Marine growths was not an issue on these floats, intermeittently in the water, but more on the fuselage, which was generally immerse deeper, especially in tropical environments. In fact after a prolongated stay in water, taking off with a crusty hull could cause so much drag as to prevent even taking off when fully loaded. One solution was to stay at a freshwater mooring to kill this salty water fauna and flora, then washed away when taking off or scrub it off on land. The underside of the fuselage indeed was not painted with the usual chemical red primer of ships. Tha could have added some extra weight and complicate access to some parts.Repairs & Damage control

In case of lower hull damage, the was on board all the necessary material to patch it and fill bullet holes with any materials at hand before landing. It happened also that the pilots generally trie to beach their aircraft in the worst case, just as a ship. The fuselage was designed to stay afloat in case of two compartments filled to compromise buoyancy. It happened that some pilots also landed on grass airfields ashore. It was generally devastating, but one was repaired and could fly again. The Mk V added to this fuel lines safety, as the latter could ne dumped from retractable pipes extending to the bomb room side, aft bulkhead. This dumping could be done airborne or while floating, but in that case always downwind away in case it caught fire.Apart the points seen above about the hull's underbelly care the engines were pretty standards and needed just average maintenance and n extreme case no maintenance at all apart having oil and gas at all times. These were bulletproof engines, and shared parts with a lot of other models so servicing was not an issue. Plus the nature of these large flying boat was, like the patrol bombers, to be based in UK or close to good facilities given their range. It was more complicated in the Mediterranean though.

Variants

Mark I

First "S.25", designed to integrate 37 mm. cannon in the nose, later deleted. Pegasus X engines rated for 709 kW (950 HP) then Pegasus XXII engines from March 1938. Production from October 1938. The wings accommodates six drum fuel tanks for 9,200 liters (2,430 US gallons), 4 fuel tanks behind the rear wing spar for a total of 11,602 liters payload 900 kgs (2,000 pounds). All metal but control surfaces (fabric cover). Two decks, six bunks, galley with stove, 9 in crew. Quad MG tail, twin nose, hand-held guns mounted in the fuselage ports. Improvements comprised a twin MG forward, new propellers, and pneumatic rubber wing de-icing boots.Mark II/III

August 1941: Production moved to the Mark II (43 made by Blackburn) featuring:-Reworked "step" blow the hull to "unstick" more easily.

-Pegasus XVIII engines with two-speed superchargers rated for 794 kW (1,065 HP).

-Tail turret FN.4A with four 7.7 mm and 2x more ammunition (1,000 rds/gun).

-Late production Mark FN.7 dorsal turret behind the wings, twin 7.7 mm.

December 1941: Sunderland Mark III:

-Revised hull configuration for improved seaworthiness

-Hull "step" to better "unstick" replaced by a smooth curve.

-Empty weight 14,970 kilograms (33,000 pounds), max loaded weight 26,310 kilograms (58,000 pounds)

-Main variant, mass production of 461 by Short Rochester, Belfast, Lake Windemere (new plant) as well as 170 by Blackburn.

Mid-1942:

-Adoption of the ASV Mk III radar replacing the Mzrk II, detected by U-Boat Metox systems (Mark IIIa).

-4+ machine guns, fixed forward fuselage for the Pilot to strafe U-Boats.

-2x 0.50 (12.7 mm) guns either side. on Mark Is (retrofit)

-Adoption of hydrostatically fused 250 lb (110 kg) depth charges

-Adoption of ammunition boxes of 10 and 25 lb (5 and 11 kg) anti-personnel bombs to hit FLAK

-Optimisations for night patrols but no Leigh lights.

-Instead, 1-in (25.4 mm), electrically initiated flares, dropped via rear chute

Mark IV (2 prototypes, see later)

The Sunderland Mark IV was born from the Air Ministry Specification R.8/42, calling for an improved Sunderland, powered by the Bristol Hercules engines and with better defensive armament among other for service in the Pacific. Two prototypes built but it was so different as to finally be renamed by the factory S.45 "Seaford" (see below). Changes comprised a new, larger and stronger wing, larger tailplanes, longer fuselage, new hull form and new panoramic glasshouse. Heavy armament of only .50 inch (12.7 mm) machine guns and 20 mm Hispano cannon. 30 Seaford ordered, only eight completed before cancellation, seeing only trials.Mark V (155 made)

The last production version camed from reports essentially. Pilots complained more and more about the Sunderland being underpowered as weight creeped up over the years, especially after installation of a radar. The Pegasus engines were taxed constantly and overheated fast, maintenance was more complicated and they were replaced regularly. In fact service availability dropped. The Sunderland Crews of the RAAF already trialeled the installation in ad hoc nacelles of the larger but more powerful Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp engines. These 14-cylinder engines provided a massive boost at 1,200 hp (895 kW). They powered the two engined Catalinas and Dakotas and would not be a burden for logistics and maintenance. Two Mark III leaving production lines by early 1944 were fitted in a workshop by these engines. Trials conducted in February and proved it was a right idea. The nacelled needed to be redesigned, fuel lines partly redistributed and recalibrated, but was considered whorth the modifications without much disruption.Thes engines also turned the propeller too fast and were replaced by new, larger Hamilton Standard's Hydromatic constant-speed and fully feathering propellers, whjch was not possible before. The Mark V as a result had greater performance and kept the same range. In fact they were so powerful that even with two engines down, the Sunderland would stay in the air and not experience a drop in altitude. Production thus was switched and Twin Wasp obtained. However the whole process lasted for a year. It's only in February 1945 that the first Mark V reached the frontline. Armament did not changed bu these adopted the new centimetric ASV Mark VI C radar. 155 Sunderland were made, 33 Mark IIIs converted before contracts were cancelled. Though with so many hulls still on construction, the last ones were still delivered as late as June 1946 for a grand total of 777, versus 756 in wartime.

⚙ Sunderland Mark III specifications | |

| Empty Weight | 34,500 lb (15,649 kg) |

| Gross Weight | 58,000 lb (26,308 kg) |

| Max Takeoff weight | c30 tonnes |

| Lenght | 85 ft 4 in (26.01 m) |

| Wingspan | 112 ft 9.5 in (34.379 m) |

| Height | 32 ft 10.5 in (10.020 m) |

| Wing Area | 1,487 sq ft (138.1 m2) |

| Airfoil | Göttingen 436 mod |

| Engines | 4× Bristol Pegasus XVIII 9-cyl. ACRPE, 1,065 hp (794 kW) |

| Props | 3-bladed de Havilland constant-speed propellers, 12 ft 9 in (3.89 m) |

| Top Speed | 210 mph (340 km/h, 180 kn) at 6,500 ft (2,000 m) |

| Cruise Speed | 178 mph (286 km/h, 155 kn) at 5,000 ft (1,500 m) |

| Range | 1,780 mi (2,860 km, 1,550 nmi), 13 hours endurance |

| Climb Rate | 720 ft/min (3.7 m/s) |

| Ceiling | 17,200 ft (5,200 m) |

| Wing Loading | 39 lb/sq ft (190 kg/m2) |

| Power/mass | 0.073 hp/lb (0.120 kW/kg) |

| Armament | Max 12x 0.303 MG Browning, FN 7, FN 11 turrets, some 0.5-in HMG |

| Armament | 2,000 lb (910 kg) bombs, mines, depth charges |

| Crew | 9–11 (2 pilots, 1 radio operator, 1 navigator, 1 engineer, 1 bomb-aimer, 3-5 gunners) |

Service

The RAF received its first Sunderland Mark I in June 1938. The second produced flew to Singapore. By September 1939, the RAF Coastal Command operated 40 Sunderlands Mark I. Before ASW organization was setup, Sunderlands were used for search and rescue of crews of torpedoed ships. On 21 September 1939, two Sunderlands rescued 34 from KENSINGTON COURT in heavy seas. As ASW organization progressed, theur performances against U-Boats also did. It's an RAAF (Royal Australian Air Force) Sunderland which in fact scored the first registered U-Boat kill of the war on 17 July 1940. As Sunderlands became more common over the seas, their encountered with the Lufwaffe went up as well. On 3 April 1940, while off Norway the most famous encountered solidified the legend of this new flying boat. Long story short, the lone Mark I was attacked by no less than six German Junkers Ju 88 fighters, fitted woth a nose with MGs and a cannon. It managed to shoot one down, damage another (forced landing) and drove off the rest. If at their return the Germans nicknamed it the "Fliegende Stachelschwein (Flying Porcupine)" the written source however was never found.

Sunderlands also found their use in the brighter Mediterranean and even performed better to a point. Their engines suffered greatly however; They notably evacuated countles troops during the evacuations after the German invasion of Crete, while it's a Sunderland that reported the Regia Marina's position at anchor in Taranto before the famous 11 November 1940 night raid by Swordfishes. Another day, also off Crete, one Sunderland broke the record book by rescuing no less than 82 men in one go, on a calm sea. All in all, the Sunderland was used by the No. 10, 40 and 461 Squadron RAAF, between the Med and Pacific, but also the 422-423 Sqn. RCAF, 5 and 490 Squadron RNZAF, No.35 Squadron SAAF, and No. 330 Squadron RNoAF (Norwegian crews) and the Free French No. 343 Squadron RAF, later Escadrille 7FE and postwar, notaby in Indochina, the Flottille 1FE, 7F, 27F, 12S, 50S, 53S, mostly Mark Vs for the latter. Commonality of engines with the Catalina and Dakota were much appreciated. The RAF Coastal Command operated them in the No. 8, 95, 119, 201, 202, 204, 205, 209, 210, 228, 230, 240, 246, 259, 270 Sqn. and the 235 Operational Conversion Unit RAF.

As the war intensified in the Atlantic, so the Sunderland, the numerous Mark IIIs in particular went up to higher gear to relentless hunts over long hours. Thanks to their max 13h flights, pilots tried to reach the "black pot" where the range of air cover and of some destroyers generally stopped. From October 1941, Sunderlands were fitted with ASV Mark II "Air to Surface Vessel" radar, a primitive low frequency system with a wavelength of just 1.5 m connected to "stickleback" Yagi antennas on top of the rear fuselage with four smaller in two rows along the sides. There was a single receiving aerial under each wing outboard of the float, angled outward as well and other systems appered over the years. They proved more and more able to detect U-Boats in appealing weather, the norm in the north Atlantic. Sunderland pilots indeed braves the winter, so confident they were in their massive machines.

However by mid-1942 the Germans started to bring up counter-measures. Some U-Boat were equipped with the passive Metox radar detection device and were alerted by the proximity of a sunderland. This gave them time to dive. Once the new detector started to be generalized, sightings just dropped drastically. However another measure was more radical and enabled the U-Boats to stay longer and even not diving at all: Heavy FLAK. Most carried twin 20 mm AA guns and later the VIIC/M42 had a 37 mm and up to four 20 mm, not counting the "U-FLAK" that were deployed as well. Against this, the Sunderland were armed as well. The cal. .05 M1920 Browning heavy machine guns located in the flanks could be used as anti-personal weapons and the late Mark III pilots also received four LMGs in the nose to strafe the U-boat before a low altitude bombing pass. Later, they also received anti-personal grenades just to harrass the crews.

In 1943-44, the fight even intensified at night with rolling patrols of alternative aicraft per squadrons or even specialized night squadrons. They came equipped with flares and better radars, notably some that could not be intercepted by U-Boats. U-Boats mostly stayed surfaced by night and just caught up with convoys when starting their attacks, diving only when they had no other choice. Sunderland crews were briefed by Convoys captains to circle around certain positions were U-Boats wen known to gather and changes their tactics on the fly (pun intended) for better results. When a Sunderland was around, captains were condifent that a ship left behind, torpedoed would have its crew picked up rapidly by the four-engines guardian angel.

The Mark V was designed to fight in the Pacific but overall saw little service in it. A few were sent from 1941 and when the Mark V production ramped up, a few squadrons were constituted but IJN submarine activity was all but gone. Instead, Sunderlands mostly performed SAR missions, picking up pilots in particular in and around the late combat theaters, in particular Okinawa and during the last Australian and commonwealth operations notably in Burma-Malaya, especially as transports. On that chapter as the war in Europe ended, more and more were converted as transports, unarmed.

In late 1942 already the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) obtained six Mark IIIs, de-militarised as mail carriers to Nigeria and India. They could carry either 22 passengers and 2 tons of freight or 16 passengers and 3 tons of freight. They were also used by RAF as VIP transports from Poole to Lagos and Calcutta. Six more Mark IIIs were obtained in 1943 and performed better for cruise speed. By late 1944, the RNZAF acquired four Mk IIIs already modified for transport and postwar they were used by New Zealand's National Airways Corporation on the "Coral Route" until 1947.

Many companies bought stocked Sunderlands postwar a low price. BOAC obtained much more demilitarized Mark IIIs and made better accommodations in three configurations. One had a promenade deck, another had 24 seats, even 16 sleeping berths. 29 of these flew in 1945. In February 1946, one made a record 35,313-mile survey from Poole to Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Tokyo (206 flying hours), a record at the time. The company improved on its model which gave the postwar Short Sandringham. The Mk.I had earlier Pegasus engines, the Mk.II Twin Wasp engines (like the Mark III and Mark V). verall postwar they were used by the Aerolíneas Argentinas, Ansett Flying Boat Services, Antilles Airboats (US Virgin Islands), Aquila Airways, Compañía Aeronáutica Uruguaya S.A. (CAUSA), Compañía Argentina de Aeronavegación Dodero, Det Norske Luftfartselskap (DNL), Qantas, Trans Oceanic Airways, TEAL (Tasman Empire Airways Ltd, New Zealand).

In Museums Today

-ML814, Mark III, converted to Mark V, used for passenger at Kermit Weeks' Fantasy of Flight in Florida, US.-ML824 in Hangar 1 RAF Museum London Hendon, ex-French Navy, left Brest to Pembroke on 24 Mar 1961.

-ML796 t Imperial War Museum Duxford in Cambridgeshire.

-NJ203 RAF Mark IV/Seaford I S-45 NJ203. at Oakland Aviation Museum, Cal.

-NZ4111 at the Chatham Islands. ex RNZAF until 1959.

-NZ4112 Hulk at Hobsonville Yacht Club until 1970, Cockpit and front now at Ferrymead Aeronautical Society Inc. Christchurch NZ

-NZ4115 previous BOAC G-AHJR at the Museum of Transport and Technology in Auckland, New Zealand.

Succession: The Short Shetland

The SHORT SHETLAND was a planned successor of the Sunderlmand. This was a High-speed, very long-range, heavily-armed reconnaissance flying-boat. Internally it was called Short S.35; designed to OR.91, in compliance with Specification R. 14/40. Two prototypes were ordered after selection of Short design in favour of competing Saro S.41, Saro being made responsible for detail design and manufacture of wing. First flight was on December 14, 1944, with the prototype DX166. It was at that stage largest British aircraft to have flown.

It was powered by four 2,400 hp Bristol Centaurus VII engines, with a crew of 11, armed with nose, dorsal and tail turrets with at least a pair of 0.50-in (12.7-mm) heavy MGs each, and a massive bomb load of 18,000 Ib (8,165 kg). The war ended before completion of the second prototype. Top speed was superior to the Sunderland at 263 mph (424 km/h) despite a gross weight of 125,000 Ib (56,700 kg). Its record span was of 150ft 4 in (46.75 m) for 110 ft (33.5 m) long. The tail, floats, struts and many parts were borrowed from the Sunderland.

Plans

Gallery

Author's illustrations: Types and liveries

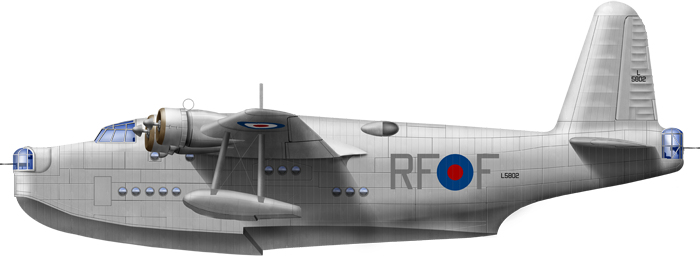

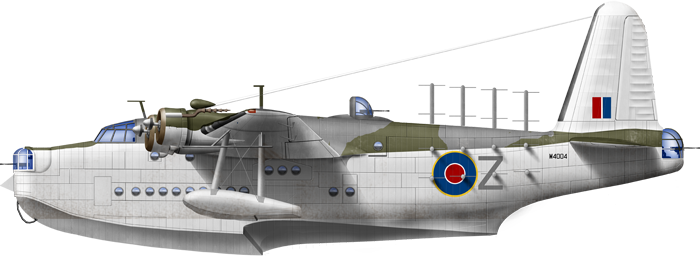

Prewar Mark I, 204 Sqn. GR RAF

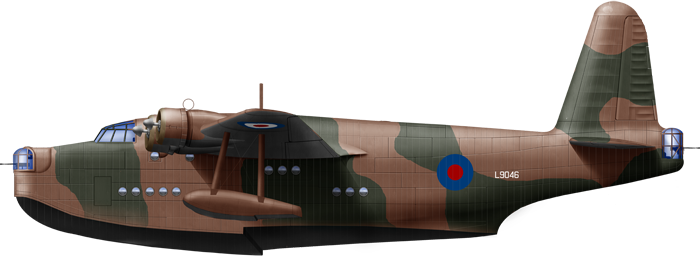

Mark I with early camo scheme

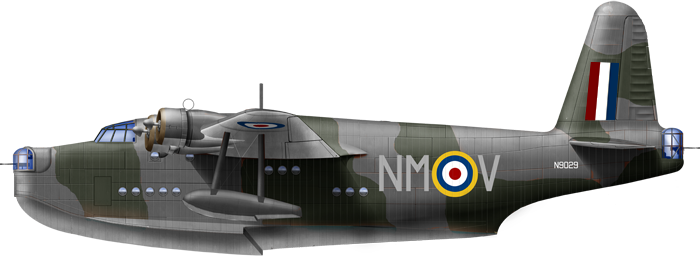

Mark I 228 Sqn. Alexandria, Egypt 1941

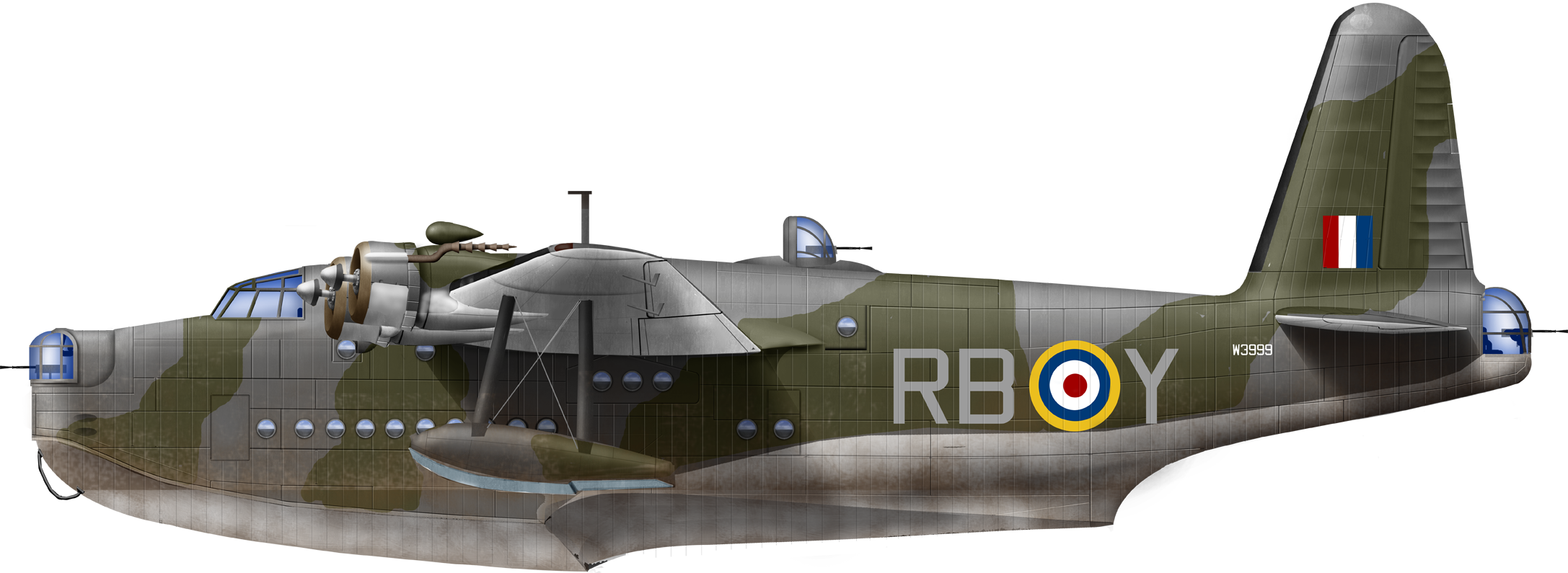

Mark III, unknown unit, 1943

Mark IIIa 201 Sqn. 1943

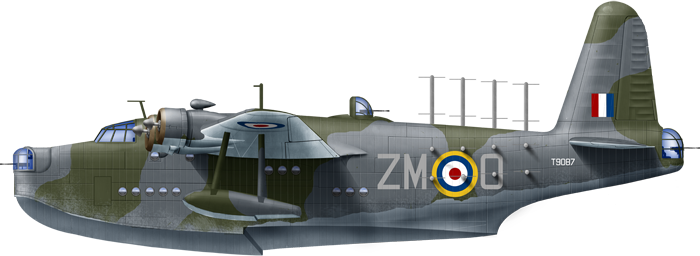

Mark III, 6th from Rochester Works January 1942 with ASV Mk.II radar

Mark III from 10 Sqn. RAAF Pembroke Dock 1942

Mark III 40 Sqn RAAF Port Moresby 1945

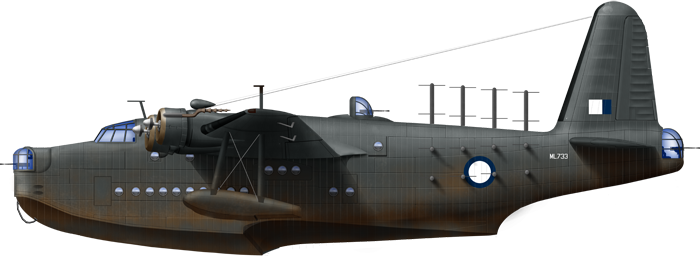

Mark III 330 Sqn (Norwegian Crew) 1945

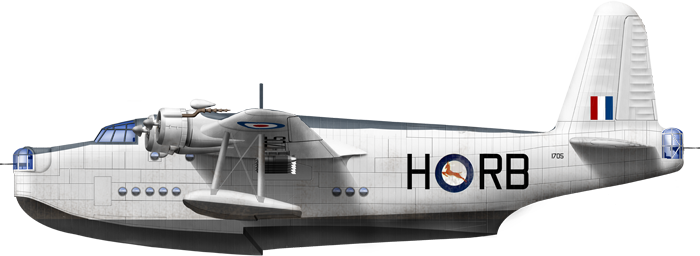

Mark V, 35 Sqn. Durban 1952

Mark V Flotille 7F, 1952

Additional photos (Pinterest, all)

Links and resources

Barnes C.H. and Derek N. James. Shorts Aircraft since 1900. London: Putnam, 1989.Bowyer, Chaz. Sunderland at War. Shepperton, Surrey, UK: Ian Allan Ltd., 1976.

Bridgman, Leonard, ed. "The Short S-25 Sunderland." Jane's Fighting Aircraft of WWII. Studio, 1946.

Buttler, Tony, AMRAeS. Short Sunderland (Warpaint Series No. 25). Milton Keynes, UK: Hall Park Books Ltd.

Eden, Paul, ed. The Encyclopedia of Aircraft of WW II. Leicester, UK: Silverdale Books/Bookmart Ltd, 2004.

Evans, John. The Sunderland Flying-boat Queen, Volume I-III. Pembroke Dock, Pembrokeshire: Paterchurch Publications, 1987-2004.

Grant, Mark. Australian Airpower 1914 to 1945. Marrickville, NSW: Topmill P/L, 1996.

Johnson, Brian. The Secret War. London: BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation), 1978.

Kightly, James. "Sunderland Survivors." Aeroplane, February 2009.

Lake, Jon. Sunderland Squadrons of World War 2. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2000.

Lawrence, Joseph (1945). The Observer's Book Of Airplanes. London and New York: Frederick Warne & Co.

Miller, David. U-Boats: The Illustrated History of The Raiders of The Deep. London: Brassey's Inc., 2002.

Norris, Geoffrey. The Short Sunderland (Aircraft in Profile number 189). London: Profile Publications, 1967.

Nicolaou, Stephane. Flying Boats & Seaplanes: A History from 1905. New York: Zenith Imprint, 1998.

Prins, François (Spring 1994). "Pioneering Spirit: The QANTAS Story". Air Enthusiast. No. 53. pp. 24–32.

Short Sunderland (AP1566). (Suffixes A through E for Mk I through V, -PN and Vols 1 through 4 for Pilots Notes, General Description, Maintenance, Overhaul and Parts Manuals). London: RAF (Air Publication), 1945.

Simper, Robert. River Medway and the Swale. Lavenham, Suffolk, UK: Creekside Publishing, 1998.

Southall, Ivan. Fly West. Woomera: Australia: Angus and Robertson, 1976.

Tillman, Barrett. Brassey's D-Day Encyclopedia: The Normandy Invasion A-Z. London: Brassey's, 2004.

Warner, Guy (July–August 2002). "From Bombay to Bombardier: Aircraft Production at Sydenham, Part One". Air Enthusiast.

Werner, H. A. Iron Coffins: A U-boat Commander's War, 1939–45. London: Cassells, 1999.

Lake, Alan. FLYING UNITS OF THE RAF – The ancestry, formation and disbandment of all flying units from 1912. England: Alan Lake, 1999

uboat.net

splashdown2.tripod.com

web.archive.org killifish.f9.co.uk

Short Shetland

airvectors.net

sixtant.net

ww2aircraft.net sunderland vs Ju88

ww2aircraft.net nickname porcupine

aviadejavu.ru

Short_Empire

Short_Sunderland

The model corner

On scalemates, all kits.- Lohner E (1913)

- Macchi M3 (1916)

- Macchi M5 (1918)

- Ansaldo ISVA (1918)

- Short S.38 (1912)

- Sopwith Baby (1916)

- Short 184 (1916)

- Fairey Campania (1917)

- Sopwith Cuckoo (1917)

- Felixstowe F.2 (1917)

- Friedrichshafen FF 33 (1916)

- Albatros W4 (1916)

- Albatros W8 (1918)

- Hanriot HD.2

- Grigorovich M5 (1915)

- Grigorovich M9 (1916)

- IJN Farman MF.7

- IJN Yokosho Type Mo

- Yokosho Rogou Kougata (1917)

- Yokosuka Igo-Ko (1920)

- Curtiss N9 (1916)

- Aeromarine 39

- Vought VE-7

- Douglas DT (1921)

- Boeing FB.5 (1923)

- Boeing F4B (1928)

- Vought O2U/O3U Corsair (1928)

- Blackburn Blackburn (1922)

- Supermarine Seagull (1922)

- Blackburn Ripon (1926)

- Fairey IIIF (1927)

- Fairey Seal (1930)

- LGL-32 C.1 (1927)

- Fokker T.II (1921)

- Caspar U1 (1921)

- Dornier Do J Wal (1922)

- Rohrbach R-III (1924)

- Mitsubishi 1MF (1923)

- Mitsubishi B1M (1923)

- Yokosuka E1Y (1923)

- Nakajima A1N (1927)

- Nakajima E2N (1927)

- Mitsubishi B2M (1927)

- Nakajima A4N (1929)

- CANT 18

WW1

✠ K.u.K. Seefliegerkorps:

Italian Naval Aviation

Italian Naval Aviation

RNAS

RNAS

Marineflieger

Marineflieger

French Naval Aviation

French Naval Aviation

Russian Naval Aviation

Russian Naval Aviation

IJN Air Service

IJN Air Service

USA

USA

Interwar

Interwar US

Interwar US

Interwar Britain

Interwar Britain

Interwar France

Interwar France

Interwar Netherlands

Interwar Netherlands

Interwar Germany

Interwar Germany

Interwar Japan

Interwar Japan

Interwar Italy

Interwar Italy

- Curtiss SOC seagull (1934)

- Grumman FF (1931)

- Curtiss F11C Goshawk (1932)

- Grumman F2F (1933)

- Grumman F3F (1935)

- Northrop BT-1 (1935)

- Grumman J2F Duck (1936)

- Consolidated PBY Catalina (1935)

- Brewster/NAF SBN-1 (1936)

- Curtiss SBC Helldiver (1936)

- Vought SB2U Vindicator (1936)

- Brewster F2A Buffalo (1937)

- Douglas TBD Devastator (1937)

- Vought Kingfisher (1938)

- Curtiss SO3C Seamew (1939)

- Douglas SBD Dauntless (1939)

- Grumman F4F Wildcat (1940)

- F4U Corsair (NE) (1940)

- Brewster SB2A Buccaneer (1941)

- Grumman TBF/TBM Avenger (1941)

- Consolidated TBY Sea Wolf (1941)

- Grumman F6F Hellcat (1942)

- Curtiss SB2C Helldiver (1942)

- Curtiss SC Seahawk (1944)

- Grumman F8F Bearcat (1944)

- Ryan FR-1 Fireball (1944)

- Douglas AD-1 Skyraider (1945)

Fleet Air Arm

- Fairey Swordfish (1934)

- Blackburn Shark (1934)

- Supermarine Walrus (1936)

- Fairey Seafox (1936)

- Blackburn Skua (1937)

- Short Sunderland (1937)

- Blackburn Roc (1938)

- Fairey Albacore (1940)

- Fairey Fulmar (1940)

- Grumman Martlet (1941)

- Hawker sea Hurricane (1941)

- Brewster Bermuda (1942)

- Fairey Barracuda (1943)

- Fairey Firefly (1943)

- Grumman Tarpon (1943)

- Grumman Gannet (1943)

- Supermarine seafire (1943)

- Blackburn Firebrand (1944)

- Hawker Sea Fury (1944)

IJN aviation

- Aichi D1A "Susie" (1934)

- Mitsubishi A5M "Claude" (1935)

- Nakajima A4N (1935)

- Yokosuka B4Y "Jean" (1935)

- Mitsubishi G3M "Nell" (1935)

- Nakajima E8N "Dave" (1935)

- Kawanishi E7K "Alf" (1935)

- Nakajima B5N "Kate" (1937)

- Kawanishi H6K "Mavis" (1938)

- Aichi D3A "Val" (1940)

- Mitsubishi A6M "zeke" (1940)

- Nakajima E14Y "Glen" (1941)

- Nakajima B6N "Jill" (1941)

- Mitsubishi F1M "pete" (1941)

- Aichi E13A Reisu "Jake" (1941)

- Kawanishi E15K Shiun "Norm" (1941)

- Nakajima C6N Saiun "Myrt" (1942)

- Yokosuka D4Y "Judy" (1942)

- Kyushu Q1W Tokai "Lorna" (1944)

Luftwaffe

- Arado 196 (1937)

- Me109 T (1938)

- Blohm & Voss 138 Seedrache (1940)

Italian Aviation

- Savoia-Marchetti S.55

- IMAM Ro.43/44

- CANT Z.501 Gabbiano

- CANT Z.506 Airone

- CANT Z.508

- CANT Z.511

- CANT Z.515

French Aeronavale

- GL.300 (1926-39)

- Levasseur PL.5 (1927)

- Potez 452 (1935)

- Loire 210 (1936)

- Loire 130 (1937)

- LN 401 (1938)

Soviet Naval Aviation

- Shavrov SH-2 (1928)

- Tupolev TB-1P (1931)

- Beriev MBR-2 (1930)

- Tupolev MR-6 (1933)

- Tupolev MTB-1 (1934)

- Beriev Be-2 (1936)

- Polikarpov I16 naval (1936)

- Tupolev MTB-2 (1937)

- Ilyushine DB-3T/TP (1937)

- Beriev Be-4 (1940)

-

Skoda Š-328V

R-XIII Idro

Fokker C.XI W (1934)

WW2

- De Havilland Sea Vixen

- Hawker Sea Hawk

- Supermarine Scimitar

- Blackburn Buccaneer

- Hawker Sea Harrier

- Douglas A4 Skyhawk

- Grumman F9F Panther

- Vought F8 Crusader

- McDonnell-Douglas F-4 Phantom-II

- North Am. A5 Vigilante

- TU-142

- Yak 38 forger

☢ Cold War

✧ NATO

Fleet Air Arm

Fleet Air Arm

US Navy

US Navy

☭ Warsaw Pact

Merch

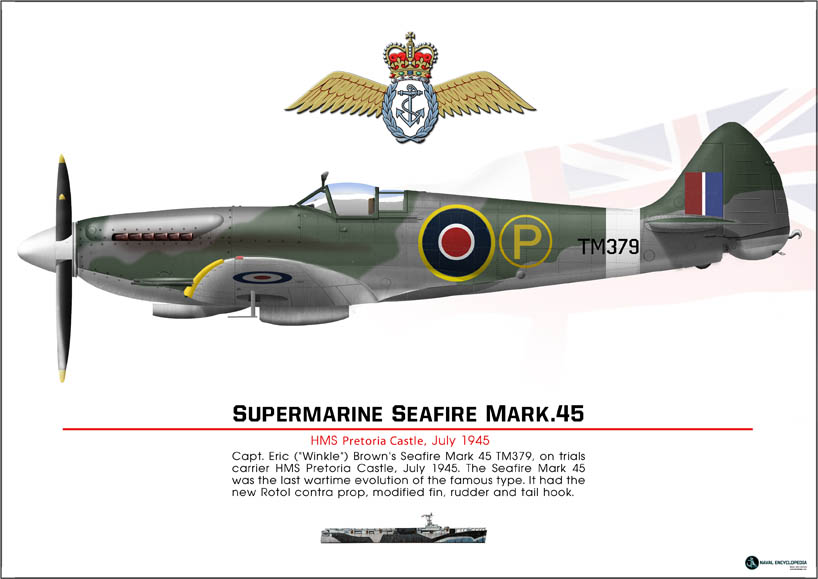

Seafire Mark 45; HMS Pretoria Castle

Zeros vs its aversaries

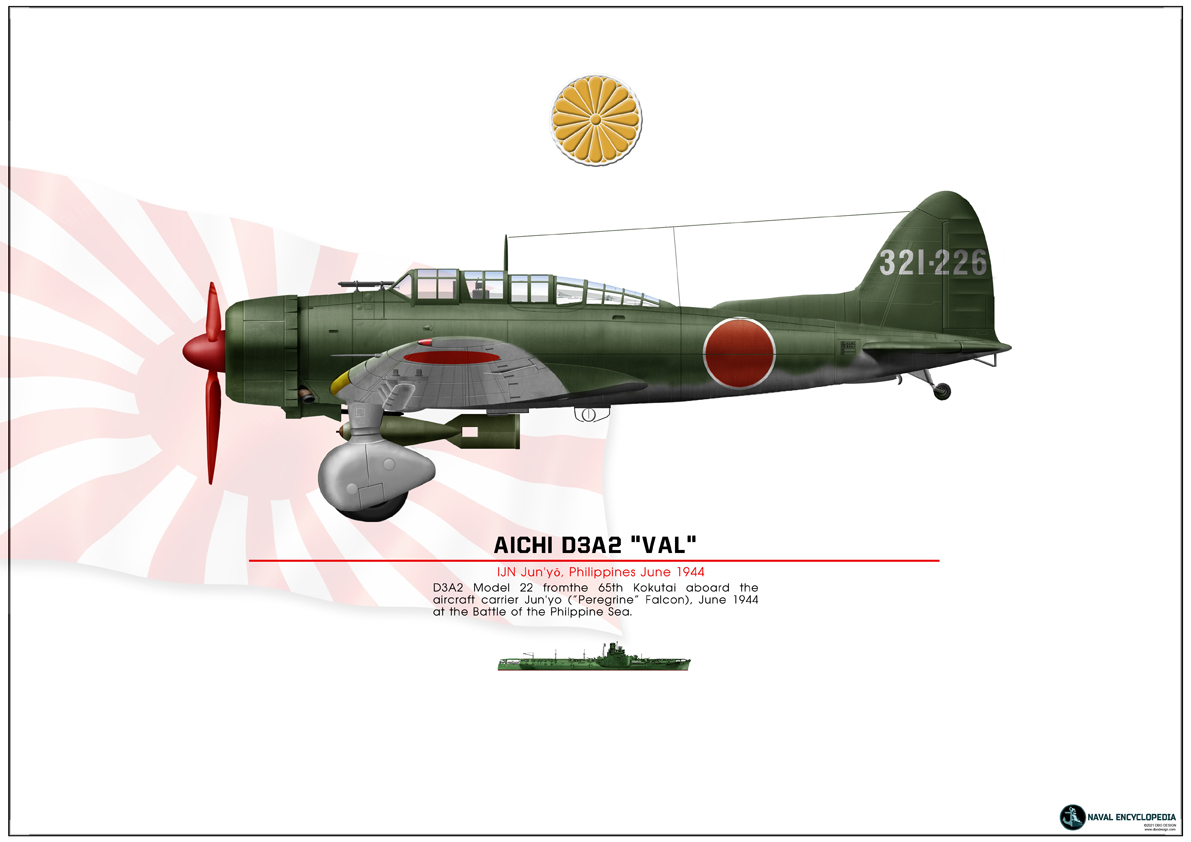

Aichi D3A “Val” Junyo

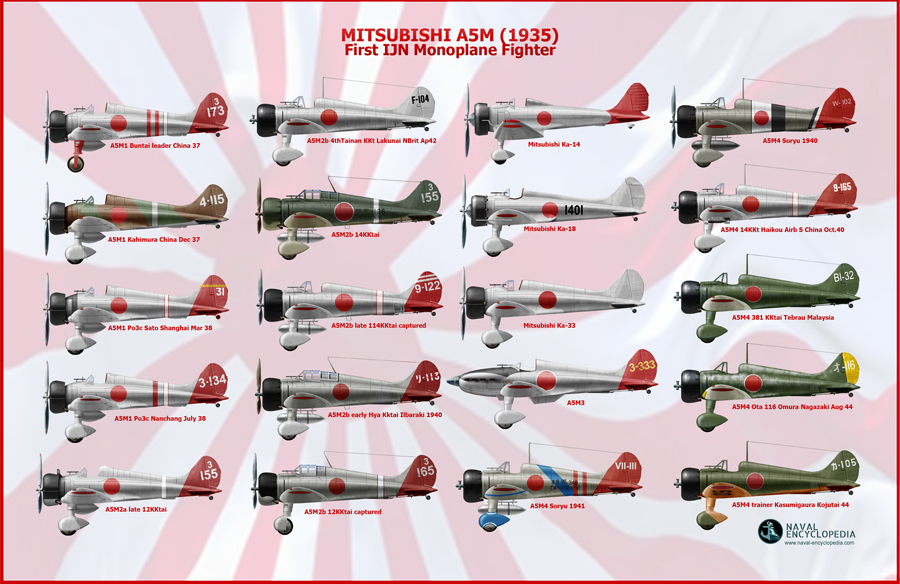

Mitsubishi A5M poster

F4F wildcat

Macchi M5

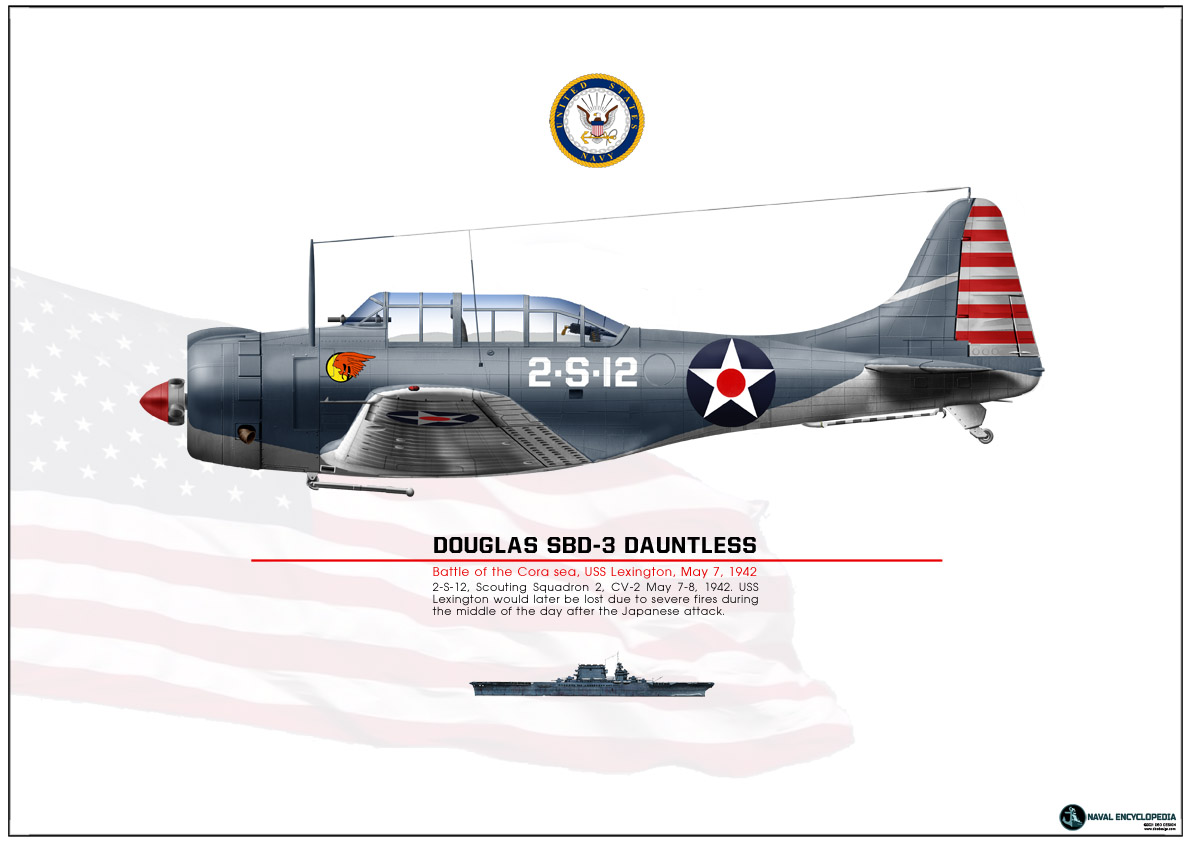

SBD Dauntless Coral Sea

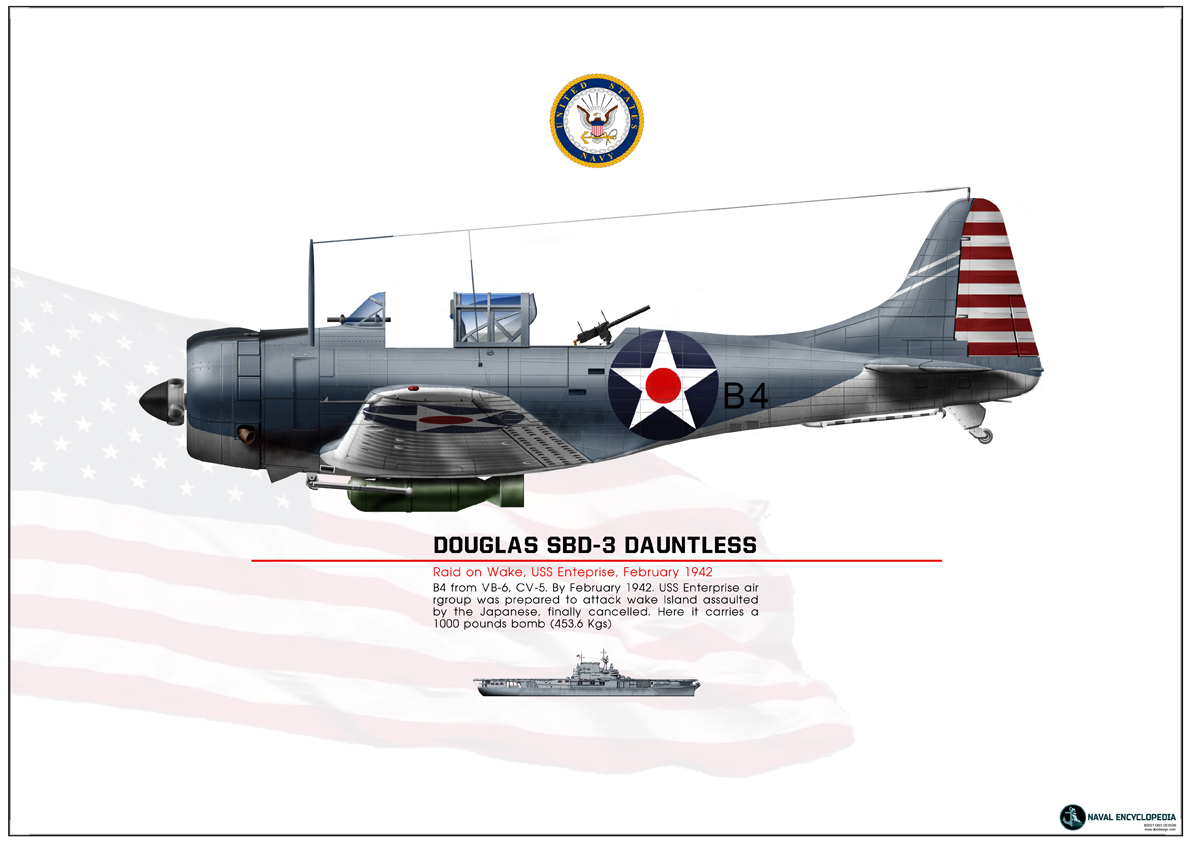

SBD Dauntless USS Enterprise

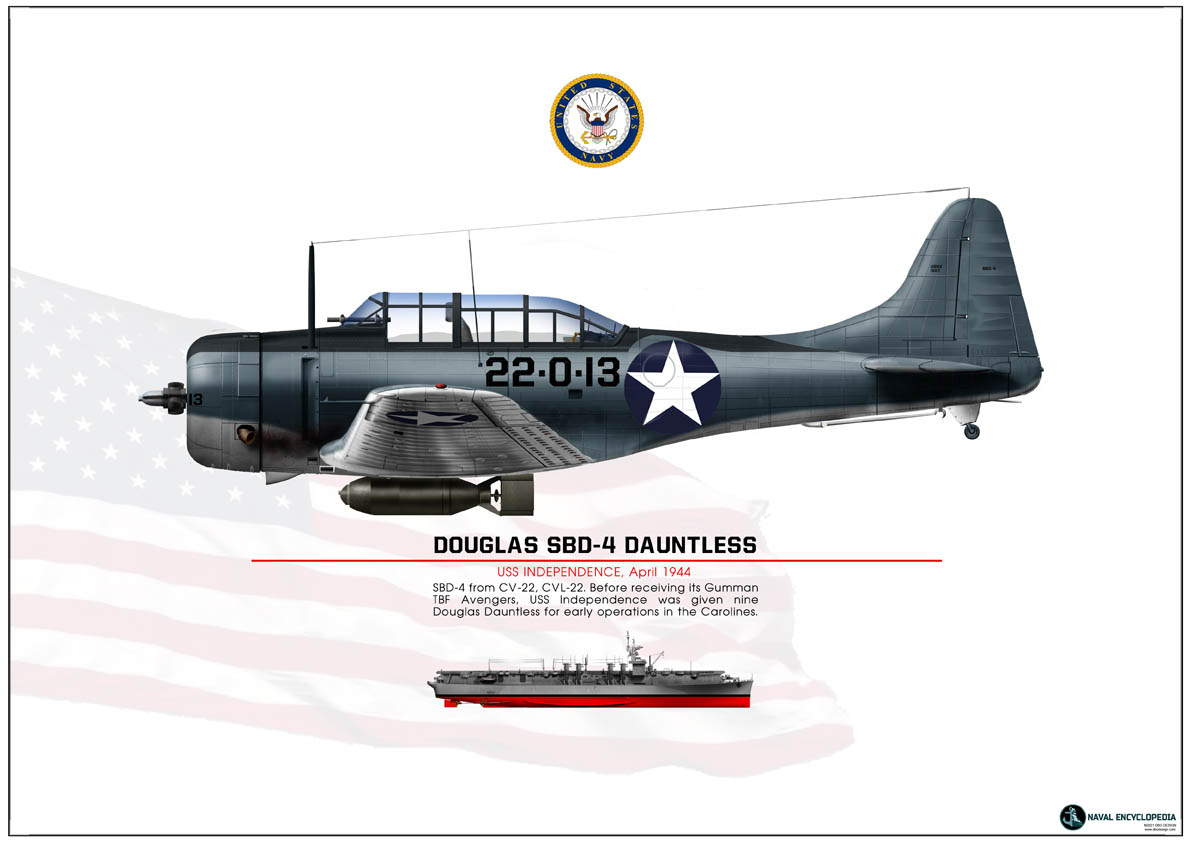

SBD-4 CV22