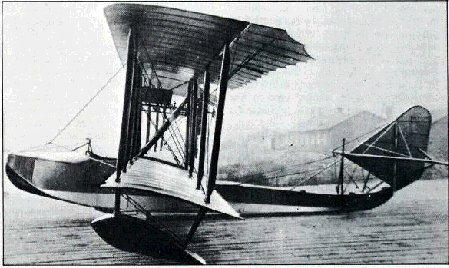

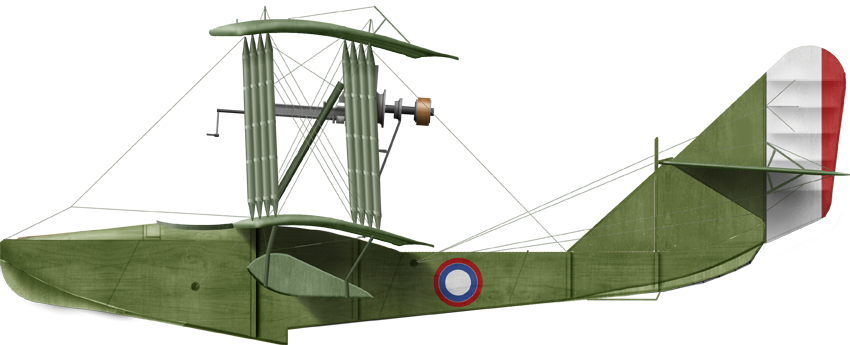

The Grigorovich M-5 (Or Shchetinin M-5) was the best Russian World War I seaplane by far. It led to a mass production with multiple variants, for a lineage that lived on until the late 1920s, and later lost to Beriev. The Grigorovitch M5, which followed two prewar prototypes and unbuilt projects, was a sturdy and dependable two-bay unequal-span biplane flying boat with a single step hull. This was the first mass production flying boat built in Russia, a name synonymous with "seaplane" in that era.

Dmitry Pavlovich Grigorovich was born in 1883 in Kyiv, Ukraine. His father worked at a sugar factory and later at the quartermaster's office of the military department. His mother, Yadviga Konstantinovna was the daughter of a doctor. He was also linked to the famous writer Dmitry Vasilyevich Grigorovich (cousin of his grandfather). After graduating from a high school, he entered the Kiev Polytechnic Institute, graduated in 1909 and moved for a year studies at the aeronautics institute in Liege, Belgium. In 1911 he moved to St. Petersburg to work as a journalist (in the same theme), publishing the magazine "Bulletin of Aeronautics". From 1912 he became technical director of "First Russian Aeronautics Partnership S.S. Shchetinin and Co." which in 1913 received a Donnet-Lévêque flying boat for repairs to her bow. Having studied the design, Grigorovich created the M-1 before the same year and worked on improving it before the summer of 1914.

Dmitry Pavlovich Grigorovich was born in 1883 in Kyiv, Ukraine. His father worked at a sugar factory and later at the quartermaster's office of the military department. His mother, Yadviga Konstantinovna was the daughter of a doctor. He was also linked to the famous writer Dmitry Vasilyevich Grigorovich (cousin of his grandfather). After graduating from a high school, he entered the Kiev Polytechnic Institute, graduated in 1909 and moved for a year studies at the aeronautics institute in Liege, Belgium. In 1911 he moved to St. Petersburg to work as a journalist (in the same theme), publishing the magazine "Bulletin of Aeronautics". From 1912 he became technical director of "First Russian Aeronautics Partnership S.S. Shchetinin and Co." which in 1913 received a Donnet-Lévêque flying boat for repairs to her bow. Having studied the design, Grigorovich created the M-1 before the same year and worked on improving it before the summer of 1914.

Her then created the experimental M-2, M-3 and M-4 in 1914, before achieving its first magnum opus, the 1915 M-5, with a production which continued until 1923. Next was the heavier M-9, as a flying boat bomber accepted in service by 1916. Then he covered another new need of the flegding Russian naval air branch, by working on a first Russian seaplane fighter, the M-11. His success led to also design land planes such as the S-1 and the S-2, the latter becoming world's first twin-tailed aircraft. He also built another bomber/recce seaplane, the twin-float M-20. In July 1917, he purchased the plant of S. S. Shchetinin where he had previously worked and by 1918

After its nationalization by the Soviets following the revolution (he did not embrace the cause), he briefly became the head of the design department of "Krasny Pilot". But suspicion about his loyalty had him fleeing from Petrograd to the native Crimea still controlled by White Russians. He successively went to Kyiv, Odessa, Taganrog and Sevastopol and while in Taganrog, he designed yet another seaplane fighter MK-1 "Rybka", which like all hhis earlier projects remained on paper.

In 1922, Grigorovich returned to Moscow and given his skills, he was promoted to head the design bureau of GAZ No.1 plant (former "Duks"), and developed the first Soviet fighters I-1 and I-2 as well as the reconnaissance aircraft R-1. In early 1924 her moved to Leningrad's "Krasny Pilot" plant, formerly his own, trying to revive it and organize the Department of Marine Experimental Aircraft Construction (OMOS). By late 1927, the OMOS team however was forcibly transferred to Moscow and became OPO-3. He spent the rest of his career on experimental models such as the MR-1, MR-2, MR-3 naval reconnaissance aircraft, MU-1 and MU-2 training aircraft, ROM-1 and ROM-2 long-range naval reconnaissance aircraft, MM-1 twin-float "naval destroyer", MT-1 naval torpedo bomber.

On August 31, 1928, Grigorovich was arrested by the OGPU to give his pasts and suspicions of loyalties. He was convicted on September 20, 1929, sentenced to 10 years of labor camp. However, from December 1929 to 1931 while in Butyrka prison, he worked with fellow engineer, also imprisoned, N. N. Polikarpov at the "sharashka" future TsKB-39 OGPU under A. G. Goryanov-Gorny and helping create the Polikarpov I-5 fighter. Amnestied on July 8, 1931 since his Plant No. 39 was awarded the Order of Lenin he received a certificate of the Central Executive Committee and a bonus of 10,000 rubles, the continued work in the Central Design Bureau on new experimental models and became a professor of the aircraft design department. He died of cancer in 1938, buried at the Moskow's Novodevichy Cemetery, then fully rehabilitated on July 1, 1993. As a young aircraft designer, Dmitry Pavlovich Grigorovich completed his first flying boat, M-1("M" standing for "Morskye" or "naval") by late 1913. The hull was inspired by the 1912 Donnet-Leveque, but much more pure in lines. The inspiratory model was sometimes spelled "Donnay-Levek" and was a two-seater in tandem. The M1 measured 7.4 m in length, 9.5 m in wingspan for a wing area of 18.2 m², and empty weight of 420 kg and take of mass (max) of 620 kg. It was powered by a Gnome rotary engine, 37 kW (50 hp). First tests were not successful and led to redesigns. He shortened the nose by about one meter, altered the wing profile along the same as the Farman F.16, and reduced the hull step from 20 cm to 8 cm. His autumn 1913 flight was successful and it showed improved handling. These flights went until December 1914, but then it crashed in an accident, putting an end to its development. In between, he already started with on the larger M2.

As a young aircraft designer, Dmitry Pavlovich Grigorovich completed his first flying boat, M-1("M" standing for "Morskye" or "naval") by late 1913. The hull was inspired by the 1912 Donnet-Leveque, but much more pure in lines. The inspiratory model was sometimes spelled "Donnay-Levek" and was a two-seater in tandem. The M1 measured 7.4 m in length, 9.5 m in wingspan for a wing area of 18.2 m², and empty weight of 420 kg and take of mass (max) of 620 kg. It was powered by a Gnome rotary engine, 37 kW (50 hp). First tests were not successful and led to redesigns. He shortened the nose by about one meter, altered the wing profile along the same as the Farman F.16, and reduced the hull step from 20 cm to 8 cm. His autumn 1913 flight was successful and it showed improved handling. These flights went until December 1914, but then it crashed in an accident, putting an end to its development. In between, he already started with on the larger M2.

During the summer and autumn of 1914, Grigorovich worked on a new, larger model, which had a raised rear triangular fuselage section and a new tail equipped with a skid, called the "shovel". The lower wings were installed 1 meters above the hull with its stronger engine support frame. A single M-2 was built, which flown several times during the summer and fall of 1914 and beyond. Essentially this was another step to create further prototypes, until it too, crashed on October 10, 1915, damaged beyond repair. It showed that further work was required to improve the overall design.

During the summer and autumn of 1914, Grigorovich worked on a new, larger model, which had a raised rear triangular fuselage section and a new tail equipped with a skid, called the "shovel". The lower wings were installed 1 meters above the hull with its stronger engine support frame. A single M-2 was built, which flown several times during the summer and fall of 1914 and beyond. Essentially this was another step to create further prototypes, until it too, crashed on October 10, 1915, damaged beyond repair. It showed that further work was required to improve the overall design.

After this series of prototypes, gradually improved, Grigorovitch eventually designed the M-5, in the spring of 1915. It was urgent still, as the Empire of Russia was now at war with the German Empire, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires all at once. In the Baltic and Black Sea, air cover was sorely lacking as Russian lacked the models needed in quantity and quality. Most of the models that flew at the time were indeed either the US Curtiss Model K or French FBA flying boats. But the supply starved out after the war broke out.

After this series of prototypes, gradually improved, Grigorovitch eventually designed the M-5, in the spring of 1915. It was urgent still, as the Empire of Russia was now at war with the German Empire, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires all at once. In the Baltic and Black Sea, air cover was sorely lacking as Russian lacked the models needed in quantity and quality. Most of the models that flew at the time were indeed either the US Curtiss Model K or French FBA flying boats. But the supply starved out after the war broke out.

Designer D. P. Grigorovich made his ideal two-seater flying boat M-5 by the spring of 1915 after constant improvements. Already in April, it had its first combat flight. It was an improvement of both the M3 and M4, taking and combining the best features of both and improving all aspects of the design. Since the Russian Naval air Branch, created in May 1912 lacked numbers, the arrival of the new Grigorovitch M5 which in demonstration flights impressed the attendance, and it was greenlighted for production as soon as possible. Construction was carried out in a brand-new facility and in fairly large series, superior to any prior model in Russian inventory.

To reach perfection, Grigorovitch increased area of the lower wing, kept a concave step but with a reduced height in the centre to 7cm and in width, down to 14cm. Its cheekbones had skids to help unsticking when powering through water. The M-5 had good seaworthiness compared to all previous modes, light and easy to control. Wooden parts were fastened with screws, up to 15,000 for the entire hull, with all work being done manually.

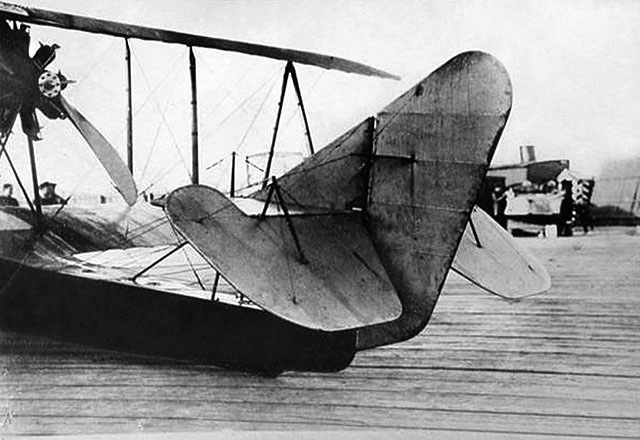

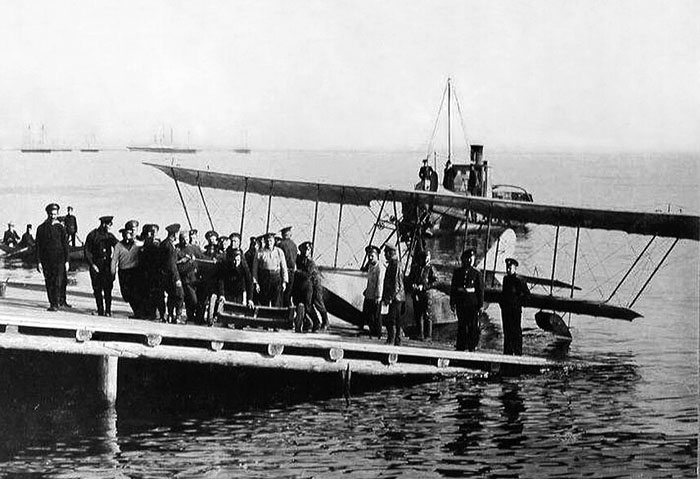

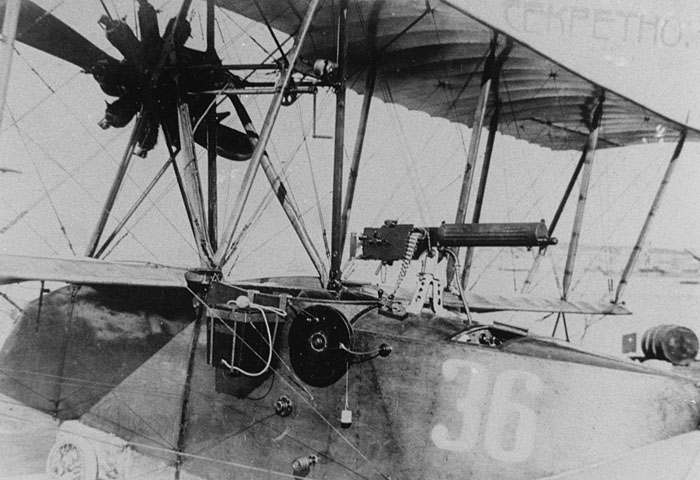

In total, the "Emperor's Military Air Fleet" (Russian naval aviation) received 183 M5s. On April 12, 1915, an M5 made its first combat flight. From July 1915 to June 1917 alone, 71 were delivered to the Black Sea Fleet of which 60 were sent to flying schools. Some M-5s served until the end of the Civil War. Until 1923, about 300 aircraft were manufactured, leading to the discrepancies among authors on the final figure. Grigorovich in the M5 made a highly seaworthy hull, yet combining with excellent flight characteristics. It could both land and take off in waves up to 0.5 m, or be launched from a landing platform. Its bottom was refined in order not to "stick" to the water for take off, a common problem among seaplanes. The M-5 and all its qualities remained in service as a naval reconnaissance aircraft, and from 1916, as a training model, while operational flying boats were mostly of the new M9 type, the bulk of all Grigorovitch models (and of Russian seaplanes in WWI). The M-5 was of wooden construction, with a hull covered in plywood, wings and tailplane in wooden framing, covered in fabric. Aft of its belly step to "unstick" when taking off, the hull tapered sharply into little more than a gracious gooseneck boom, supporting a cross-type fin and rudder tail unit, braced by struts and wires. It was normally powered by a 100 hp Gnome Monosoupape engine (since the M3) mounted in a pusher configuration between the wings. Some later due to supply shortages, also used the 110 hp Le Rhône, or towards the end of the war, 130 hp Clerget engines. Pilot and observer were seated forward side-by-side in a large cockpit, with the observer being provided with an axial-mounted single 7.62 mm Vickers machine gun on pintle. Meaning it could be used by the pilot also. It was however rarely mounted.

The M-5 was of wooden construction, with a hull covered in plywood, wings and tailplane in wooden framing, covered in fabric. Aft of its belly step to "unstick" when taking off, the hull tapered sharply into little more than a gracious gooseneck boom, supporting a cross-type fin and rudder tail unit, braced by struts and wires. It was normally powered by a 100 hp Gnome Monosoupape engine (since the M3) mounted in a pusher configuration between the wings. Some later due to supply shortages, also used the 110 hp Le Rhône, or towards the end of the war, 130 hp Clerget engines. Pilot and observer were seated forward side-by-side in a large cockpit, with the observer being provided with an axial-mounted single 7.62 mm Vickers machine gun on pintle. Meaning it could be used by the pilot also. It was however rarely mounted.

The M-5 biplane used a wooden ash frame covered in plywood, 3 mm thick for the side skin panels, up to 5-6 mm on deck. The redan on the bottom was made of 10 mm plywood. For extra strength in places, the sheathing thickness reached 5 mm. The fuselage was assembled using brass screws and lead and white zinc elements. The skin joints were reinforced with plywood overlays, riveted with copper rivets, all to avoid corrosion. The lower seams were reinforced with copper foil, joints were soldered with tin. The fuselage outer skin was covered with colorless varnish, the inside with drying oil for waterproofing. During assembly, a special "marine glue" using a compound of ammonia were used to increased water resistance of the structure. However, construction was quite unhealthy... Transverse and longitudinal sets were connected with clamps made of 3 mm plywood.

The wings were two-spar and thin braced with a main structure made of pine, upper and lower wings connected crosswise with metal braces, and to the bow with more braces. The tail unit attached above the curved tail section was placed on pipe struts. The stabilizer was all wooden with struts, and connected with metal braces to the keel. The stabilizer angle was set on the ground before flight. Rudders and keel were welded from thin-walled steel pipes, covered with doped fabric. The tail unit was not rigid, and the tail twisted and vibrated from propeller blows, but never broke.

The design comprised two-spar, braced wings of similar shape but smaller for the lower plane, larger up, but not yet sequiplane. These had a very thin profile, about 4% of the wing chord. The upper and lower wings were connected crosswise with metal braces, and the latter also connected the wings to the bow. Control cables for the rudders and ailerons were laid outside. The tail unit used a frame in metal pipe struts, yet very light, not strictly rigid. It could twist noticeably on a turn and even being shake by the propeller blow. The wooden stabilizer haad braces under the rear spar connected with metal braces to the keel. The stabilizer angle could be changed before the flight. Rudders and keel were welded from thin steel pipes with several wooden ribs, all covered with fabric.

The rotary air-cooled engine "Gnome Monosoupape" (Single valve) was a well known French prewar engine which first ran in 1913 and was sold with a licence to Russia prior to the war. It was also produced by Italy and Britain. It also powered the Airco DH2 and Nieuport 28 among other models. This was a rudimentary model, simple yet costly to built and maintain, and had however its drawbacks, on top of the fact of being a rotary (the whole unit turned with the propeller), creating powerful side forces. It needed to be precisely balanced and setup and consumed a lot of oil. It had an output of 100 hp, turning a fixed pitch wooden two-bladed propeller. It was installed on a motor frame located in the space between the central interwing struts. Forward of it was a handle for manual engine start by the pilot or observer standing up. A hand pump was used to supply petrol, creating excess pressure in the fuel tank behind the pilot. Landing speed was 70 km/h, top speed 105 km/h above water, with a practical ceiling of 3300 m, flight time 4 hours. Takeoff weight was 960 kg, with a payload of 300 kg.

This radial air-cooled engine had its Petrol supplied under pressure (excess air pressure via a hand pump) and its fuel tank was located behind the pilot's cabin. The M-5 overall was a well-thought-out and harmonious design ensuring good flight characteristics, simple and safe control. It provided a sufficient margin of safety in normal operation and takeoff or taxiing even in challenging sea conditions. It had no vices and was well-balanced and without surprises. All these qualities made it ideal as a training aircraft.

Still, it was outperformed by 1916 by every single fighter and its payload was quite low. Top speed, just over 100 kph made it a sitting duck, if caught, and the machine gun, when mounted, had limited traverse. On the way to create the M9, its magnum opus, Grigorovich however repeatedly tried to improve flight characteristics by installing a more powerful engine, but consistently failed.

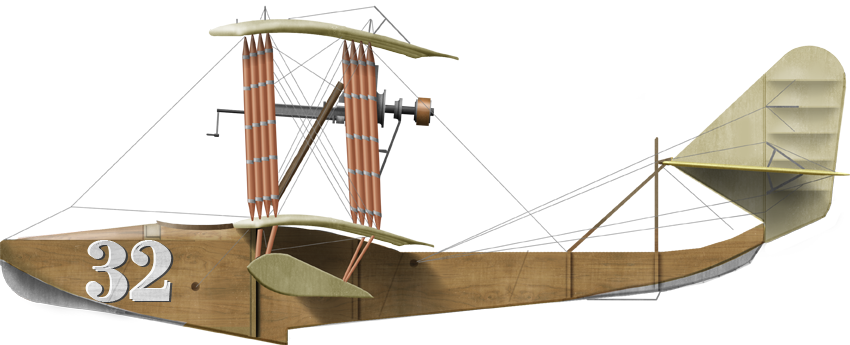

Imperial Russian Navy & White Army from 1917

Imperial Russian Navy & White Army from 1917

Finnish Air Force

Finnish Air Force

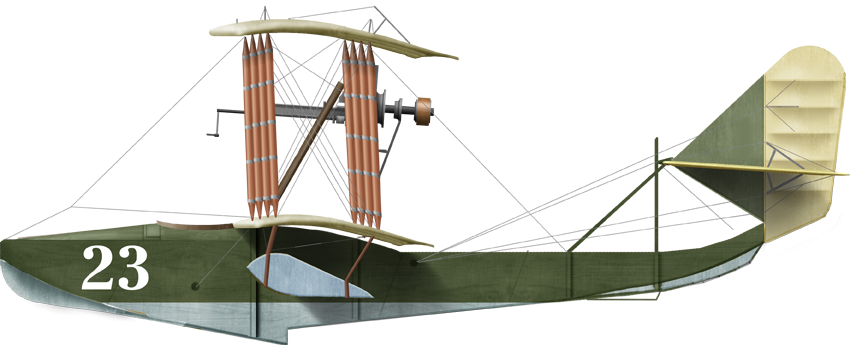

Russian SFSR: Red Army

Russian SFSR: Red Army

Soviet Naval Aviation

Soviet Naval Aviation

Most of the M-5s were active in the Black Sea, the remainder in the Baltic, initially with the Imperial Russian naval air arm, for reconnaissance, then from 1916 as trainer. Then from 1918 it was used on both sides in the Russian Civil War. Some stayed in service until the late 1920s as trainers, as well as for reconnaissance or as utility aircraft. One was captured by the Finns at Kuokkala in 1918. It became the first seaplane of the Finnish Air Force, used allegedly until 1919. Another survives today also in the Istanbul Aviation Museum in Turkey, preserved in Ottoman Air Force markings and also captured on the Black Sea.

Most of the M-5s were active in the Black Sea, the remainder in the Baltic, initially with the Imperial Russian naval air arm, for reconnaissance, then from 1916 as trainer. Then from 1918 it was used on both sides in the Russian Civil War. Some stayed in service until the late 1920s as trainers, as well as for reconnaissance or as utility aircraft. One was captured by the Finns at Kuokkala in 1918. It became the first seaplane of the Finnish Air Force, used allegedly until 1919. Another survives today also in the Istanbul Aviation Museum in Turkey, preserved in Ottoman Air Force markings and also captured on the Black Sea.

Design & Development

About Dmitry Pavlovich Grigorovitch

Dmitry Pavlovich Grigorovich was born in 1883 in Kyiv, Ukraine. His father worked at a sugar factory and later at the quartermaster's office of the military department. His mother, Yadviga Konstantinovna was the daughter of a doctor. He was also linked to the famous writer Dmitry Vasilyevich Grigorovich (cousin of his grandfather). After graduating from a high school, he entered the Kiev Polytechnic Institute, graduated in 1909 and moved for a year studies at the aeronautics institute in Liege, Belgium. In 1911 he moved to St. Petersburg to work as a journalist (in the same theme), publishing the magazine "Bulletin of Aeronautics". From 1912 he became technical director of "First Russian Aeronautics Partnership S.S. Shchetinin and Co." which in 1913 received a Donnet-Lévêque flying boat for repairs to her bow. Having studied the design, Grigorovich created the M-1 before the same year and worked on improving it before the summer of 1914.

Dmitry Pavlovich Grigorovich was born in 1883 in Kyiv, Ukraine. His father worked at a sugar factory and later at the quartermaster's office of the military department. His mother, Yadviga Konstantinovna was the daughter of a doctor. He was also linked to the famous writer Dmitry Vasilyevich Grigorovich (cousin of his grandfather). After graduating from a high school, he entered the Kiev Polytechnic Institute, graduated in 1909 and moved for a year studies at the aeronautics institute in Liege, Belgium. In 1911 he moved to St. Petersburg to work as a journalist (in the same theme), publishing the magazine "Bulletin of Aeronautics". From 1912 he became technical director of "First Russian Aeronautics Partnership S.S. Shchetinin and Co." which in 1913 received a Donnet-Lévêque flying boat for repairs to her bow. Having studied the design, Grigorovich created the M-1 before the same year and worked on improving it before the summer of 1914.

Her then created the experimental M-2, M-3 and M-4 in 1914, before achieving its first magnum opus, the 1915 M-5, with a production which continued until 1923. Next was the heavier M-9, as a flying boat bomber accepted in service by 1916. Then he covered another new need of the flegding Russian naval air branch, by working on a first Russian seaplane fighter, the M-11. His success led to also design land planes such as the S-1 and the S-2, the latter becoming world's first twin-tailed aircraft. He also built another bomber/recce seaplane, the twin-float M-20. In July 1917, he purchased the plant of S. S. Shchetinin where he had previously worked and by 1918

After its nationalization by the Soviets following the revolution (he did not embrace the cause), he briefly became the head of the design department of "Krasny Pilot". But suspicion about his loyalty had him fleeing from Petrograd to the native Crimea still controlled by White Russians. He successively went to Kyiv, Odessa, Taganrog and Sevastopol and while in Taganrog, he designed yet another seaplane fighter MK-1 "Rybka", which like all hhis earlier projects remained on paper.

In 1922, Grigorovich returned to Moscow and given his skills, he was promoted to head the design bureau of GAZ No.1 plant (former "Duks"), and developed the first Soviet fighters I-1 and I-2 as well as the reconnaissance aircraft R-1. In early 1924 her moved to Leningrad's "Krasny Pilot" plant, formerly his own, trying to revive it and organize the Department of Marine Experimental Aircraft Construction (OMOS). By late 1927, the OMOS team however was forcibly transferred to Moscow and became OPO-3. He spent the rest of his career on experimental models such as the MR-1, MR-2, MR-3 naval reconnaissance aircraft, MU-1 and MU-2 training aircraft, ROM-1 and ROM-2 long-range naval reconnaissance aircraft, MM-1 twin-float "naval destroyer", MT-1 naval torpedo bomber.

On August 31, 1928, Grigorovich was arrested by the OGPU to give his pasts and suspicions of loyalties. He was convicted on September 20, 1929, sentenced to 10 years of labor camp. However, from December 1929 to 1931 while in Butyrka prison, he worked with fellow engineer, also imprisoned, N. N. Polikarpov at the "sharashka" future TsKB-39 OGPU under A. G. Goryanov-Gorny and helping create the Polikarpov I-5 fighter. Amnestied on July 8, 1931 since his Plant No. 39 was awarded the Order of Lenin he received a certificate of the Central Executive Committee and a bonus of 10,000 rubles, the continued work in the Central Design Bureau on new experimental models and became a professor of the aircraft design department. He died of cancer in 1938, buried at the Moskow's Novodevichy Cemetery, then fully rehabilitated on July 1, 1993.

Prototypes: Grigorovitch M1 and M2

M1 (1913)

As a young aircraft designer, Dmitry Pavlovich Grigorovich completed his first flying boat, M-1("M" standing for "Morskye" or "naval") by late 1913. The hull was inspired by the 1912 Donnet-Leveque, but much more pure in lines. The inspiratory model was sometimes spelled "Donnay-Levek" and was a two-seater in tandem. The M1 measured 7.4 m in length, 9.5 m in wingspan for a wing area of 18.2 m², and empty weight of 420 kg and take of mass (max) of 620 kg. It was powered by a Gnome rotary engine, 37 kW (50 hp). First tests were not successful and led to redesigns. He shortened the nose by about one meter, altered the wing profile along the same as the Farman F.16, and reduced the hull step from 20 cm to 8 cm. His autumn 1913 flight was successful and it showed improved handling. These flights went until December 1914, but then it crashed in an accident, putting an end to its development. In between, he already started with on the larger M2.

As a young aircraft designer, Dmitry Pavlovich Grigorovich completed his first flying boat, M-1("M" standing for "Morskye" or "naval") by late 1913. The hull was inspired by the 1912 Donnet-Leveque, but much more pure in lines. The inspiratory model was sometimes spelled "Donnay-Levek" and was a two-seater in tandem. The M1 measured 7.4 m in length, 9.5 m in wingspan for a wing area of 18.2 m², and empty weight of 420 kg and take of mass (max) of 620 kg. It was powered by a Gnome rotary engine, 37 kW (50 hp). First tests were not successful and led to redesigns. He shortened the nose by about one meter, altered the wing profile along the same as the Farman F.16, and reduced the hull step from 20 cm to 8 cm. His autumn 1913 flight was successful and it showed improved handling. These flights went until December 1914, but then it crashed in an accident, putting an end to its development. In between, he already started with on the larger M2.

M2 (1914)

During the summer and autumn of 1914, Grigorovich worked on a new, larger model, which had a raised rear triangular fuselage section and a new tail equipped with a skid, called the "shovel". The lower wings were installed 1 meters above the hull with its stronger engine support frame. A single M-2 was built, which flown several times during the summer and fall of 1914 and beyond. Essentially this was another step to create further prototypes, until it too, crashed on October 10, 1915, damaged beyond repair. It showed that further work was required to improve the overall design.

During the summer and autumn of 1914, Grigorovich worked on a new, larger model, which had a raised rear triangular fuselage section and a new tail equipped with a skid, called the "shovel". The lower wings were installed 1 meters above the hull with its stronger engine support frame. A single M-2 was built, which flown several times during the summer and fall of 1914 and beyond. Essentially this was another step to create further prototypes, until it too, crashed on October 10, 1915, damaged beyond repair. It showed that further work was required to improve the overall design.

M3 (1914)

The next M-3, was not entirely successful. In essence, it was a slightly modified M-2, but with a more powerful 100 hp Gnome-Monosoupape engine. It hull was essentially similar, but the wing profile was changed, and test flights showed that even with this new layout, performance did not improve compared to the M-2. Its seaworthiness also remained unsatisfactory. It did not crash but was quickly sidelined and cannibalized.M4 (1914)

Grigorovich's the M-4 was in turn a modified version of the M-3, with the same engine stripped from the M-3. The wing profile as changed again, and the hull had its shaped modified. The stabilizer was now made incorporating a screw lift, making it possible to change its angle while in flight. The whole endeavour over less than two years and four prototypes was outstanding, though. Grigorovich had to combine the best aerodynamic qualities inherent in any aircraft, while combining the ruggedness of a boat, with specific properties such as buoyancy, stability, unsinkability, seaworthiness. During all this time, without literature or even calculations helping in the design, Grigorovitch had to literally "feel his way" to the optimal design. These hard lessons culminated to the eventually awesome M-5 flying boat, a landmark in naval history, as far as Russia was concerned.Development of the M5

After this series of prototypes, gradually improved, Grigorovitch eventually designed the M-5, in the spring of 1915. It was urgent still, as the Empire of Russia was now at war with the German Empire, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires all at once. In the Baltic and Black Sea, air cover was sorely lacking as Russian lacked the models needed in quantity and quality. Most of the models that flew at the time were indeed either the US Curtiss Model K or French FBA flying boats. But the supply starved out after the war broke out.

After this series of prototypes, gradually improved, Grigorovitch eventually designed the M-5, in the spring of 1915. It was urgent still, as the Empire of Russia was now at war with the German Empire, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires all at once. In the Baltic and Black Sea, air cover was sorely lacking as Russian lacked the models needed in quantity and quality. Most of the models that flew at the time were indeed either the US Curtiss Model K or French FBA flying boats. But the supply starved out after the war broke out.

Designer D. P. Grigorovich made his ideal two-seater flying boat M-5 by the spring of 1915 after constant improvements. Already in April, it had its first combat flight. It was an improvement of both the M3 and M4, taking and combining the best features of both and improving all aspects of the design. Since the Russian Naval air Branch, created in May 1912 lacked numbers, the arrival of the new Grigorovitch M5 which in demonstration flights impressed the attendance, and it was greenlighted for production as soon as possible. Construction was carried out in a brand-new facility and in fairly large series, superior to any prior model in Russian inventory.

To reach perfection, Grigorovitch increased area of the lower wing, kept a concave step but with a reduced height in the centre to 7cm and in width, down to 14cm. Its cheekbones had skids to help unsticking when powering through water. The M-5 had good seaworthiness compared to all previous modes, light and easy to control. Wooden parts were fastened with screws, up to 15,000 for the entire hull, with all work being done manually.

In total, the "Emperor's Military Air Fleet" (Russian naval aviation) received 183 M5s. On April 12, 1915, an M5 made its first combat flight. From July 1915 to June 1917 alone, 71 were delivered to the Black Sea Fleet of which 60 were sent to flying schools. Some M-5s served until the end of the Civil War. Until 1923, about 300 aircraft were manufactured, leading to the discrepancies among authors on the final figure. Grigorovich in the M5 made a highly seaworthy hull, yet combining with excellent flight characteristics. It could both land and take off in waves up to 0.5 m, or be launched from a landing platform. Its bottom was refined in order not to "stick" to the water for take off, a common problem among seaplanes. The M-5 and all its qualities remained in service as a naval reconnaissance aircraft, and from 1916, as a training model, while operational flying boats were mostly of the new M9 type, the bulk of all Grigorovitch models (and of Russian seaplanes in WWI).

Design of the Grigorovitch M5

The M-5 was of wooden construction, with a hull covered in plywood, wings and tailplane in wooden framing, covered in fabric. Aft of its belly step to "unstick" when taking off, the hull tapered sharply into little more than a gracious gooseneck boom, supporting a cross-type fin and rudder tail unit, braced by struts and wires. It was normally powered by a 100 hp Gnome Monosoupape engine (since the M3) mounted in a pusher configuration between the wings. Some later due to supply shortages, also used the 110 hp Le Rhône, or towards the end of the war, 130 hp Clerget engines. Pilot and observer were seated forward side-by-side in a large cockpit, with the observer being provided with an axial-mounted single 7.62 mm Vickers machine gun on pintle. Meaning it could be used by the pilot also. It was however rarely mounted.

The M-5 was of wooden construction, with a hull covered in plywood, wings and tailplane in wooden framing, covered in fabric. Aft of its belly step to "unstick" when taking off, the hull tapered sharply into little more than a gracious gooseneck boom, supporting a cross-type fin and rudder tail unit, braced by struts and wires. It was normally powered by a 100 hp Gnome Monosoupape engine (since the M3) mounted in a pusher configuration between the wings. Some later due to supply shortages, also used the 110 hp Le Rhône, or towards the end of the war, 130 hp Clerget engines. Pilot and observer were seated forward side-by-side in a large cockpit, with the observer being provided with an axial-mounted single 7.62 mm Vickers machine gun on pintle. Meaning it could be used by the pilot also. It was however rarely mounted.

The M-5 biplane used a wooden ash frame covered in plywood, 3 mm thick for the side skin panels, up to 5-6 mm on deck. The redan on the bottom was made of 10 mm plywood. For extra strength in places, the sheathing thickness reached 5 mm. The fuselage was assembled using brass screws and lead and white zinc elements. The skin joints were reinforced with plywood overlays, riveted with copper rivets, all to avoid corrosion. The lower seams were reinforced with copper foil, joints were soldered with tin. The fuselage outer skin was covered with colorless varnish, the inside with drying oil for waterproofing. During assembly, a special "marine glue" using a compound of ammonia were used to increased water resistance of the structure. However, construction was quite unhealthy... Transverse and longitudinal sets were connected with clamps made of 3 mm plywood.

The wings were two-spar and thin braced with a main structure made of pine, upper and lower wings connected crosswise with metal braces, and to the bow with more braces. The tail unit attached above the curved tail section was placed on pipe struts. The stabilizer was all wooden with struts, and connected with metal braces to the keel. The stabilizer angle was set on the ground before flight. Rudders and keel were welded from thin-walled steel pipes, covered with doped fabric. The tail unit was not rigid, and the tail twisted and vibrated from propeller blows, but never broke.

The design comprised two-spar, braced wings of similar shape but smaller for the lower plane, larger up, but not yet sequiplane. These had a very thin profile, about 4% of the wing chord. The upper and lower wings were connected crosswise with metal braces, and the latter also connected the wings to the bow. Control cables for the rudders and ailerons were laid outside. The tail unit used a frame in metal pipe struts, yet very light, not strictly rigid. It could twist noticeably on a turn and even being shake by the propeller blow. The wooden stabilizer haad braces under the rear spar connected with metal braces to the keel. The stabilizer angle could be changed before the flight. Rudders and keel were welded from thin steel pipes with several wooden ribs, all covered with fabric.

The rotary air-cooled engine "Gnome Monosoupape" (Single valve) was a well known French prewar engine which first ran in 1913 and was sold with a licence to Russia prior to the war. It was also produced by Italy and Britain. It also powered the Airco DH2 and Nieuport 28 among other models. This was a rudimentary model, simple yet costly to built and maintain, and had however its drawbacks, on top of the fact of being a rotary (the whole unit turned with the propeller), creating powerful side forces. It needed to be precisely balanced and setup and consumed a lot of oil. It had an output of 100 hp, turning a fixed pitch wooden two-bladed propeller. It was installed on a motor frame located in the space between the central interwing struts. Forward of it was a handle for manual engine start by the pilot or observer standing up. A hand pump was used to supply petrol, creating excess pressure in the fuel tank behind the pilot. Landing speed was 70 km/h, top speed 105 km/h above water, with a practical ceiling of 3300 m, flight time 4 hours. Takeoff weight was 960 kg, with a payload of 300 kg.

This radial air-cooled engine had its Petrol supplied under pressure (excess air pressure via a hand pump) and its fuel tank was located behind the pilot's cabin. The M-5 overall was a well-thought-out and harmonious design ensuring good flight characteristics, simple and safe control. It provided a sufficient margin of safety in normal operation and takeoff or taxiing even in challenging sea conditions. It had no vices and was well-balanced and without surprises. All these qualities made it ideal as a training aircraft.

Still, it was outperformed by 1916 by every single fighter and its payload was quite low. Top speed, just over 100 kph made it a sitting duck, if caught, and the machine gun, when mounted, had limited traverse. On the way to create the M9, its magnum opus, Grigorovich however repeatedly tried to improve flight characteristics by installing a more powerful engine, but consistently failed.

⚙ specs. | |

| Empty Weight | 660 kg (1,455 lb) |

| Max TO weight | 960 kg (2,116 lb) |

| Lenght | 8.6 m (28 ft 3 in) |

| Wingspan | 13.62 m (44 ft 8 in) |

| Height | 3,4 m (11 ft) |

| Wing Area | 37.9 m2 (408 sq ft) |

| Wing Loading | 25 kg/m2 (5.1 lb/sq ft) |

| Power/mass | 0.078 kW/kg (0.05 hp/lb) |

| Engine | Gnome 9 Type B-2 9-cyl. ACRE 75 kW (101 hp) |

| Top Speed, sea level | 105 km/h (65 mph, 57 kn) |

| Cruise Speed | |

| Range/Autonomy | 4 hours |

| Climb Rate | 1.85 m/s (364 ft/min), 1,000 m (3,281 ft) in 9.6 minutes |

| Ceiling | 3,300 m (10,800 ft) |

| Armament | 7.62 mm (0.300 in) Vickers machine gun |

| Crew | 2: Pilot, Observer/Gunner |

Models

- M-5: Main version.

- M-6: M-5 with 150 hp Sunbeam engine, only prototype.

- M-7: M-5 with rounded hull, larger keel. Prototype.

- M-8: Version with further rounded hull. Prototype

- M-9: Successor, mass produced

- M-10: Smaller version built in 1916 with a Gnome Monosoupape engine, prototype.

- M-20: Two-seat recrec with Le Rhone 89 kW (120 hp) engine (few built 1916)

Operators

Imperial Russian Navy & White Army from 1917

Imperial Russian Navy & White Army from 1917 Finnish Air Force

Finnish Air Force Russian SFSR: Red Army

Russian SFSR: Red Army Soviet Naval Aviation

Soviet Naval Aviation

Combat Records, Grigorovicth M5

Most of the M-5s were active in the Black Sea, the remainder in the Baltic, initially with the Imperial Russian naval air arm, for reconnaissance, then from 1916 as trainer. Then from 1918 it was used on both sides in the Russian Civil War. Some stayed in service until the late 1920s as trainers, as well as for reconnaissance or as utility aircraft. One was captured by the Finns at Kuokkala in 1918. It became the first seaplane of the Finnish Air Force, used allegedly until 1919. Another survives today also in the Istanbul Aviation Museum in Turkey, preserved in Ottoman Air Force markings and also captured on the Black Sea.

Most of the M-5s were active in the Black Sea, the remainder in the Baltic, initially with the Imperial Russian naval air arm, for reconnaissance, then from 1916 as trainer. Then from 1918 it was used on both sides in the Russian Civil War. Some stayed in service until the late 1920s as trainers, as well as for reconnaissance or as utility aircraft. One was captured by the Finns at Kuokkala in 1918. It became the first seaplane of the Finnish Air Force, used allegedly until 1919. Another survives today also in the Istanbul Aviation Museum in Turkey, preserved in Ottoman Air Force markings and also captured on the Black Sea.

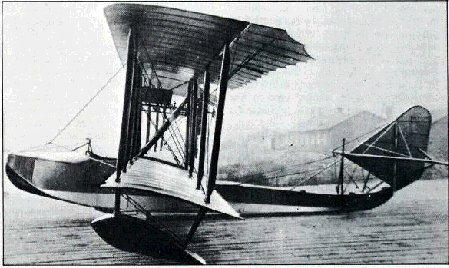

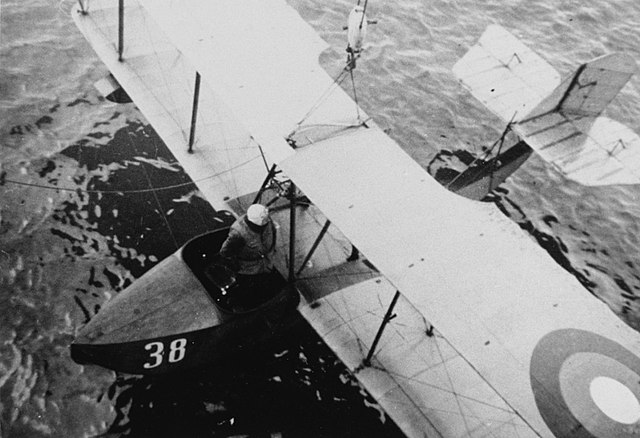

All photos: Marine Officer school, black sea fleet

Showing the pintle-mounted Machine gun.

Black sea fleet, 1915

Sources

vimpel-v.com/warhistory.org

flyingmachines.ru

secretprojects.co.uk

airwar.ru

On commons.wikimedia.org

Mikhail Maslov. Dmitry Grigorovich's Aircraft.

Shavrov VB History of Aircraft Designs in the USSR to 1938 — 3rd. — Moscow: Mashinostroenie, 1985.

Durkota, Darcey & Kulikov (1995). The Imperial Russian Air Service - Famous Pilots and Aircraft of World War 1. Flying Machines Press.

Gunston, Bill (1995). The Osprey Encyclopedia of Russian Aircraft from 1875 - 1995. Osprey Aerospace.

Heinonen, Timo: Thulinista Hornetiin - Keski-Suomen ilmailumuseon julkaisuja 3, Keski-Suomen ilmailumuseo, 1992

Kulikov, Victor (December 1996). "Le fascinante histoire des hydravions de Dimitry Grigorovitch" Avions FR

The Osprey Encyclopedia Of Russian Aircraft 1875-1995

Herbert Leonard Russian and Soviet fighters 1915-1950

- Lohner E (1913)

- Macchi M3 (1916)

- Macchi M5 (1918)

- Ansaldo ISVA (1918)

- Short S.38 (1912)

- Sopwith Baby (1916)

- Short 184 (1916)

- Fairey Campania (1917)

- Sopwith Cuckoo (1917)

- Felixstowe F.2 (1917)

- Friedrichshafen FF 33 (1916)

- Albatros W4 (1916)

- Albatros W8 (1918)

- Hanriot HD.2

- Grigorovitch M5

- IJN Farman MF.7

- IJN Yokosho Type Mo

- Yokosho Rogou Kougata (1917)

- Yokosuka Igo-Ko (1920)

- Curtiss N9 (1916)

- Aeromarine 39

- Vought VE-7

- Douglas DT (1921)

- Boeing FB.5 (1923)

- Boeing F4B (1928)

- Vought O2U/O3U Corsair (1928)

- Blackburn Blackburn (1922)

- Supermarine Seagull (1922)

- Blackburn Ripon (1926)

- Fairey IIIF (1927)

- Fairey Seal (1930)

- LGL-32 C.1 (1927)

- Caspar U1 (1921)

- Dornier Do J Wal (1922)

- Rohrbach R-III (1924)

- Mitsubishi 1MF (1923)

- Mitsubishi B1M (1923)

- Yokosuka E1Y (1923)

- Nakajima A1N (1927)

- Nakajima E2N (1927)

- Mitsubishi B2M (1927)

- Nakajima A4N (1929)

- CANT 18

WW1

✠ K.u.K. Seefliegerkorps:

Italian Naval Aviation

Italian Naval Aviation

RNAS

RNAS

Marineflieger

Marineflieger

French Naval Aviation

French Naval Aviation

Russian Naval Aviation

Russian Naval Aviation

IJN Air Service

IJN Air Service

USA

USA

Interwar

Interwar US

Interwar US

Interwar Britain

Interwar Britain

Interwar France

Interwar France

Interwar Germany

Interwar Germany

Interwar Japan

Interwar Japan

Interwar Italy

Interwar Italy

- Curtiss SOC seagull (1934)

- Grumman FF (1931)

- Curtiss F11C Goshawk (1932)

- Grumman F2F (1933)

- Grumman F3F (1935)

- Northrop BT-1 (1935)

- Grumman J2F Duck (1936)

- Consolidated PBY Catalina (1935)

- Brewster/NAF SBN-1 (1936)

- Curtiss SBC Helldiver (1936)

- Vought SB2U Vindicator (1936)

- Brewster F2A Buffalo (1937)

- Douglas TBD Devastator (1937)

- Vought Kingfisher (1938)

- Curtiss SO3C Seamew (1939)

- Douglas SBD Dauntless (1939)

- Grumman F4F Wildcat (1940)

- F4U Corsair (NE) (1940)

- Brewster SB2A Buccaneer (1941)

- Grumman TBF/TBM Avenger (1941)

- Consolidated TBY Sea Wolf (1941)

- Grumman F6F Hellcat (1942)

- Curtiss SB2C Helldiver (1942)

- Curtiss SC Seahawk (1944)

- Grumman F8F Bearcat (1944)

- Ryan FR-1 Fireball (1944)

- Douglas AD-1 Skyraider (1945)

Fleet Air Arm

- Fairey Swordfish (1934)

- Blackburn Shark (1934)

- Supermarine Walrus (1936)

- Fairey Seafox (1936)

- Blackburn Skua (1937)

- Short Sunderland (1937)

- Blackburn Roc (1938)

- Fairey Albacore (1940)

- Fairey Fulmar (1940)

- Grumman Martlet (1941)

- Hawker sea Hurricane (1941)

- Brewster Bermuda (1942)

- Fairey Barracuda (1943)

- Fairey Firefly (1943)

- Grumman Tarpon (1943)

- Grumman Gannet (1943)

- Supermarine seafire (1943)

- Blackburn Firebrand (1944)

- Hawker Sea Fury (1944)

IJN aviation

- Aichi D1A "Susie" (1934)

- Mitsubishi A5M "Claude" (1935)

- Nakajima A4N (1935)

- Yokosuka B4Y "Jean" (1935)

- Mitsubishi G3M "Nell" (1935)

- Nakajima E8N "Dave" (1935)

- Kawanishi E7K "Alf" (1935)

- Nakajima B5N "Kate" (1937)

- Kawanishi H6K "Mavis" (1938)

- Aichi D3A "Val" (1940)

- Mitsubishi A6M "zeke" (1940)

- Nakajima E14Y "Glen" (1941)

- Nakajima B6N "Jill" (1941)

- Mitsubishi F1M "pete" (1941)

- Aichi E13A Reisu "Jake" (1941)

- Kawanishi E15K Shiun "Norm" (1941)

- Nakajima C6N Saiun "Myrt" (1942)

- Yokosuka D4Y "Judy" (1942)

- Kyushu Q1W Tokai "Lorna" (1944)

Luftwaffe

- Arado 196 (1937)

- Me109 T (1938)

- Blohm & Voss 138 Seedrache (1940)

Italian Aviation

- Savoia-Marchetti S.55

- IMAM Ro.43/44

- CANT Z.501 Gabbiano

- CANT Z.506 Airone

- CANT Z.508

- CANT Z.511

- CANT Z.515

French Aeronavale

- GL.300 (1926-39)

- Levasseur PL.5 (1927)

- Potez 452 (1935)

- Loire 210 (1936)

- Loire 130 (1937)

- LN 401 (1938)

Soviet Naval Aviation

- Shavrov SH-2 (1928)

- Tupolev TB-1P (1931)

- Beriev MBR-2 (1930)

- Tupolev MR-6 (1933)

- Tupolev MTB-1 (1934)

- Beriev Be-2 (1936)

- Polikarpov I16 naval (1936)

- Tupolev MTB-2 (1937)

- Ilyushine DB-3T/TP (1937)

- Beriev Be-4 (1940)

-

Skoda Š-328V

R-XIII Idro

Fokker C.XI W (1934)

WW2

- De Havilland Sea Vixen

- Hawker Sea Hawk

- Supermarine Scimitar

- Blackburn Buccaneer

- Hawker Sea Harrier

- Douglas A4 Skyhawk

- Grumman F9F Panther

- Vought F8 Crusader

- McDonnell-Douglas F-4 Phantom-II

- North Am. A5 Vigilante

- TU-142

- Yak 38 forger

☢ Cold War

✧ NATO

Fleet Air Arm

Fleet Air Arm

US Navy

US Navy

☭ Warsaw Pact

Merch

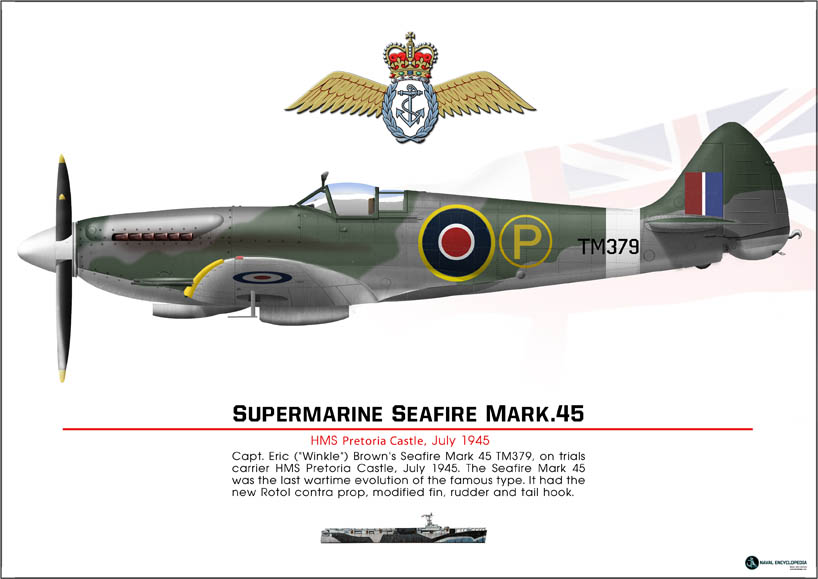

Seafire Mark 45; HMS Pretoria Castle

Zeros vs its aversaries

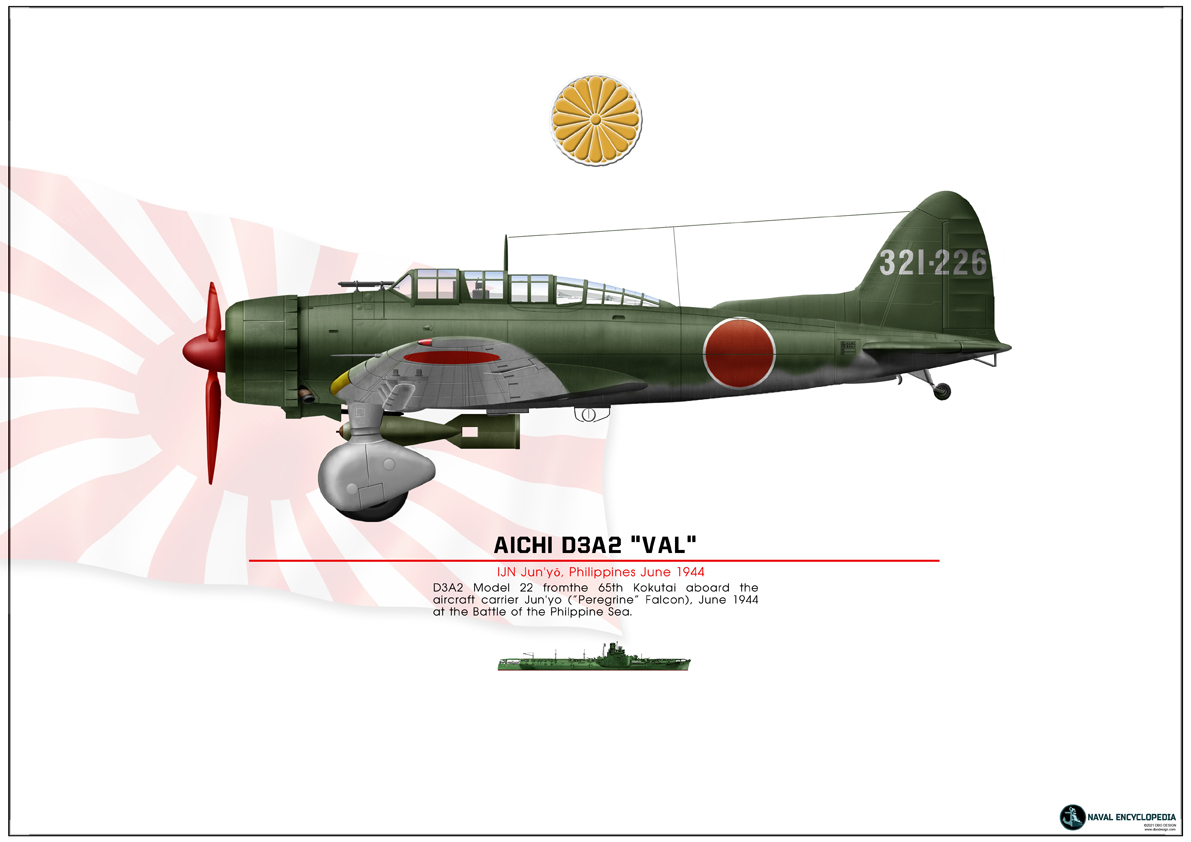

Aichi D3A “Val” Junyo

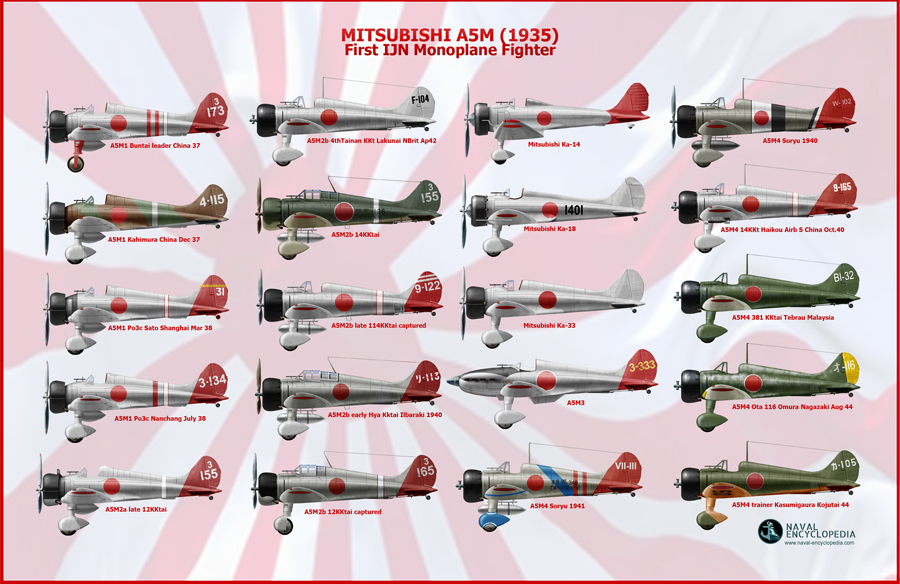

Mitsubishi A5M poster

F4F wildcat

Macchi M5

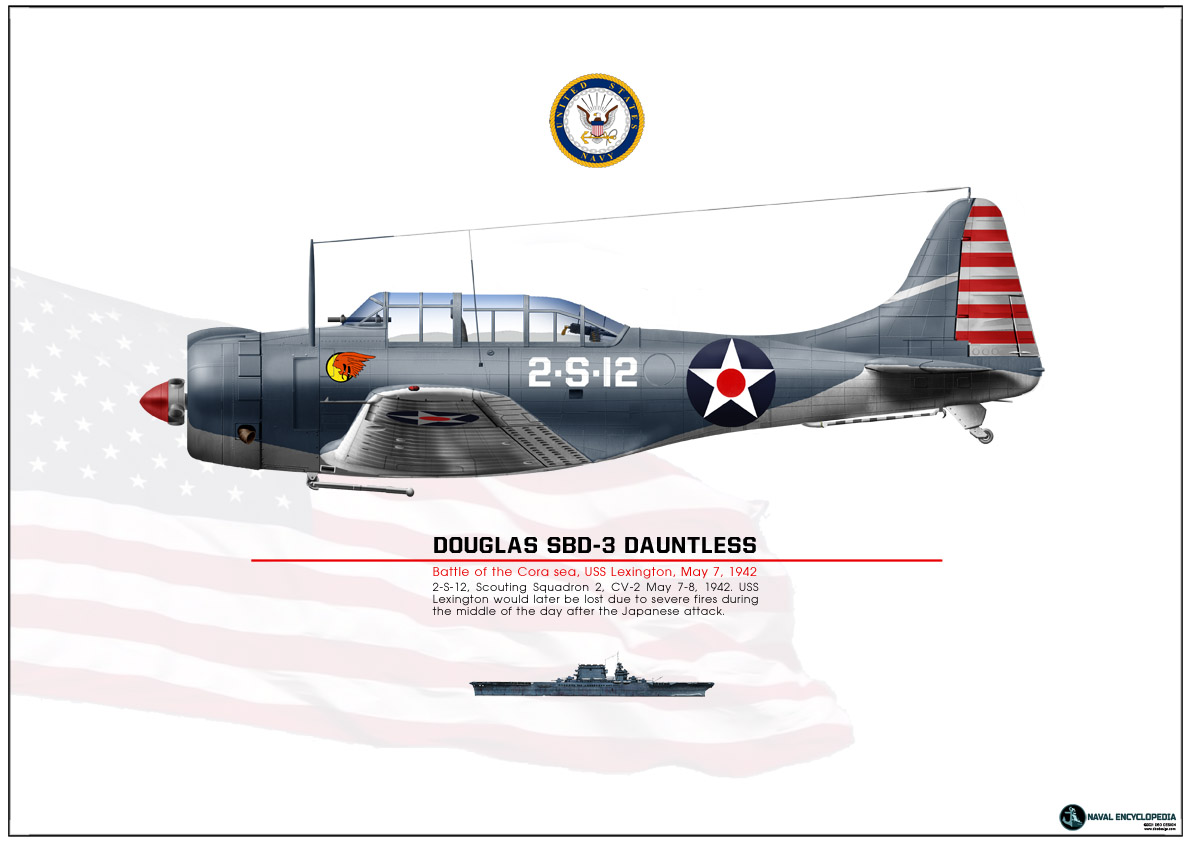

SBD Dauntless Coral Sea

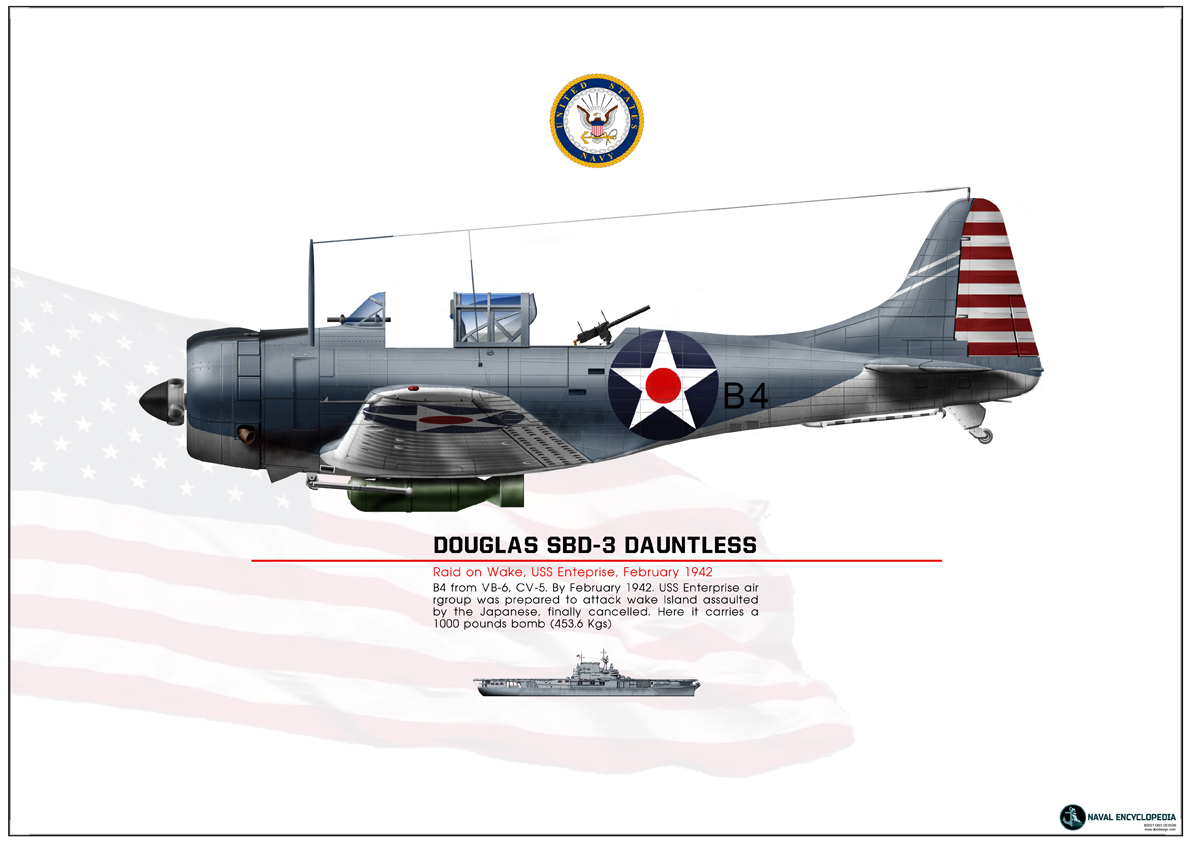

SBD Dauntless USS Enterprise

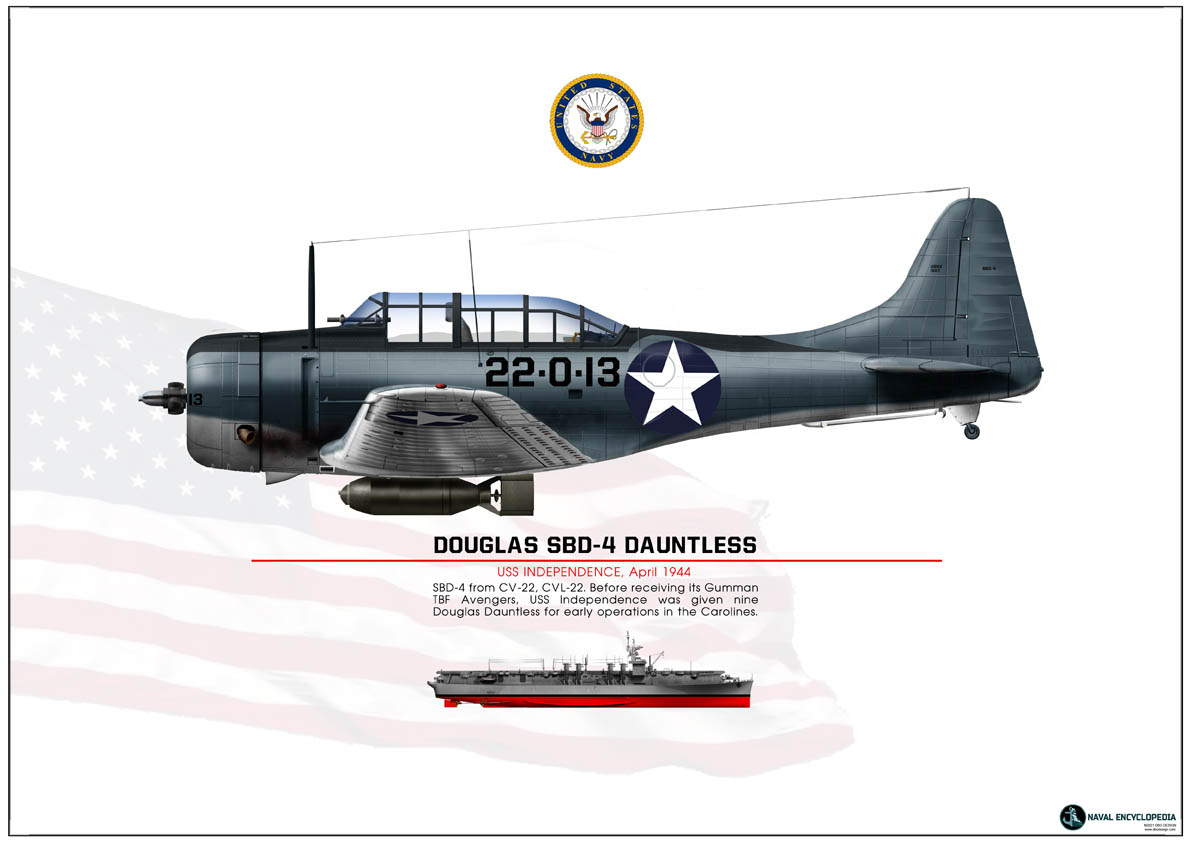

SBD-4 CV22